The Los Angeles uprising has captured the attention of the world. Just like in the early days of the George Floyd Rebellion, we are witnessing massive popular resistance outside the channels usually provided for the performance of dissent: permitted marches and City Hall rallies, voting booths and newspaper op-eds. As Trump deployed the National Guard last week, thousands gathered for unplanned demonstrations and impromptu actions. Protesters hurled chunks of concrete behind improvised barricades, set fire to the self-driving cars clogging California streets, and took direct action against the deportation regime by physically blocking ICE vans.

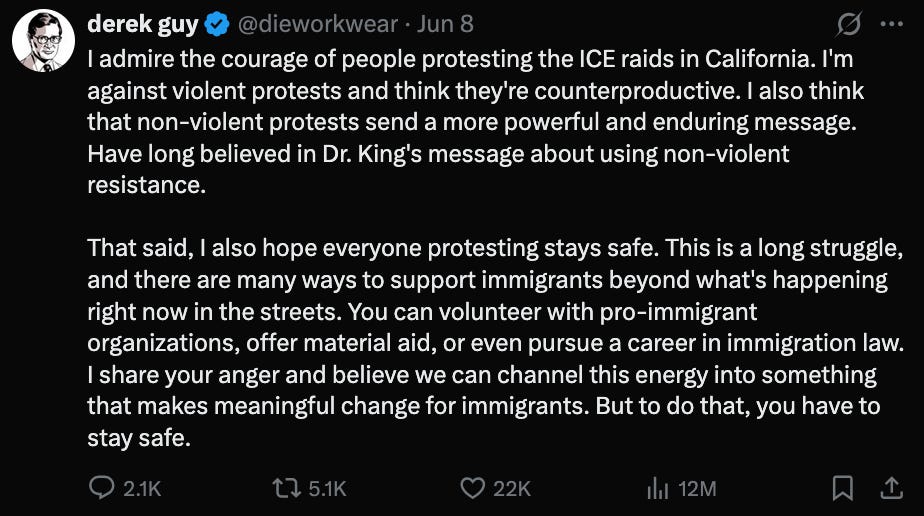

The Los Angeles rebels have inspired the world. They have also predictably inspired the finger-wagging of fair-weather allies who’d offer their full support if only the protesters were a bit more… respectable… in their politics. An instructive example was provided, strangely enough, by men’s fashion Twitter commentator Derek Guy:

Guy lauds the courage of ICE protesters while lamenting “violent protests” as “counterproductive,” predictably citing “Dr. King’s message about using non-violent resistance” to “send a more powerful and enduring message.”

The point of this article isn’t to drag the Twitter menswear guy. He’s articulating a widely held, even commonsensical, belief among US residents: nonviolent civil disobedience has a proven track record, while “violent” protest distracts from the point, invites state repression, and is ineffectual at securing reforms. These are basically gospel truths of American civil society. Belief in the ideology of nonviolent activism is as American as apple pie, foreign military interventions, and disastrous gender reveals.

If “violent” protest is obviously counterproductive, those who engage in it must be either particularly stupid or actually nefarious—outside agitators or agents provocateur. There are claims by (supposedly) well-intentioned liberals that the way to protect protest movements is to immediately turn disruptive protesters over to the very police that are being protested against. Chillingly, they view this betrayal of their fellow protesters as a kind of solidarity.

I am not making the claim that confrontational protests are free from idiots and undercovers—I’ve had the misfortune of dealing with both. But the idea that getting rowdy at a protest has a 1:1 correspondence with being an undercover cop or far-right agent is a demonstrably false claim—one that has tragic consequences.

We need to critique “nonviolence” because liberal pacifism invites violence. Not just violence in general but violence in its most objectionable form: legal violence against the most oppressed members of society. To break this down, we need to take a step back and clarify our terms. To discuss the paradox of non-violence and the puzzle of peaceful protest, we need to be clear about what violence actually is.

On violence

We use the concept of violence in flexible ways. We might talk about the linguistic violence of slurs and threats or the indirect violence of letting someone come to harm when they could have been saved them. But for the purposes of argument, let’s limit ourselves to violence in the most literal, widely accepted sense: intentional bodily harm to another human being. That’s just what the word “violence” means, and you and I and every other reasonable person can agree that, all things considered, it’s generally bad.

Here’s the thing. Much of what gets coded as “violent” protesting actually wouldn’t be considered violence at all in any other context. Vandalism, arson, breaking windows are typical forms of “violent” protest. But vandalism isn’t generally thought of as violent at all. You might object to graffiti for being illegal, unaesthetic, or anti-social—if you’re a huge nerd with no appreciation for the miracle of human creative expression—but it strains credibility to frame it as intentional physical harm to another person. Protesters in Los Angeles were condemned for “violently” redecorating self-driving cars, but breaking the glass of unoccupied vehicles isn’t typically considered violent either. Otherwise, carjacking vacant vehicles would be a violent crime.

Actions are objectively non-violent as masking up or shouting rude slogans at law enforcement all get denounced as “violence” because, as the authors of Let This Radicalize You put it:

If your tactics disrupt the order of things under capitalism, you may well be accused of violence, because ‘violence’ is an elastic term often deployed to vilify people who threaten the status quo… When state actors refer to ‘peace,’ they are really talking about order. And when they refer to ‘peaceful protest,’ they are talking about cooperative protest that obediently stays within the lines drawn by the state.

Any effective protest or direct action disrupts order, which is why the definition of “violence” suddenly balloons way beyond its normal bounds. And just like things that are normally non-violent magically become violent when directed against order, things that by any reasonable standard are extraordinarily violent get erased when they’re deployed to restore capitalist order.

Armed agents

And yes: oppositional political activity can involve direct, actual violence against the forces of order, like any ghetto uprising or armed revolt. But in a typical protest, no matter how raucous the demonstrators, only the opposing aside comes prepared to commit violent acts.

The police are the subset of public employees whose entire job is the exercise of violence. If I were to handcuff you and throw you back of my car, shoot rubber-coated bullets at your torso, or launch tear gas grenades over your head, anyone would say I’d committed violence. If I were to incarcerate you in a cell for months or years and threatened to murder you if you tried to leave, I’d be doing violence against you, as well.

A debate over protest violence that ignores the side who arrive to the protest armed with literal weapons of war is simply not serious. Those who criticize people setting fires while excusing the men jumping out of armored personnel carriers with automatic rifles cannot by any stretch of the imagination be imagined as opposed to “violence” in general. The ideology of doctrinaire nonviolence and peaceful protest is a way to split protest movements into “good” and “bad” protesters, and sacrifice the latter to actual, literal state violence.

Consider the case of Natalie from Atlanta. In June 2020, Rayshard Brooks was murdered by police outside an Atlanta Wendy’s. At a subsequent protest, the Wendy’s was set ablaze. After footage showed a white woman setting the fire, Internet sleuths went wild to track down the supposed provocateur. They succeeded, in the most tragic way imaginable. The state pinned first-degree arson charges on the woman—Rayshard Brooks’s girlfriend, Natalie White. She wasn’t an agent provocateur at all; she was the grieving girlfriend of a man just killed by the police, now arrested and locked up by the same institutions that took his life.

Natalie White didn’t physically harm a soul: she was charged with arson, not murder or even assault. In the name of peaceful protest, she was sacrificed to the same punitive carceral system that everyone in the streets in 2020 was supposedly fighting against.

State violence

If the State that protesters were confronting was itself peaceful… well, more often than not, there wouldn’t be a reason to protest in the first place.

As J. P. Hill writes in New Means:

What we have to keep in mind, always, is that protests against ICE do not ‘turn violent,’ they begin with the violence of ICE. They begin with federal agents raiding school graduations to tear families apart. They begin with ICE invading workplaces to tear people away from the lives they’ve built and the communities they live in. They begin with the lie that some people should be kidnapped, and with the immense violence inherent in that act.

Liberals like Derek Guy oppose this violence… so long as this opposition limits itself to “speaking truth to power,” “raising awareness,” or “expressing dissent” instead of actually physically opposing those carrying it out. But theatrically cruel ICE raids are symptoms of a state descending into right-wing authoritarianism. Here’s the thing about authoritarianism: it’s definitionally a political system where peaceful protest doesn’t matter. Authoritarianism is the form of power that is so insulated from democratic critique that “speaking truth” to it has no effect.

What stops authoritarian violence is actual disruption. But if actual disruption gets coded as “violence” while the real violence of the state gets a pass, the ideology of peaceful protest means only allowing ineffectual protest.

What it all means

I grew up in a strict ideologically pacifist household. I am neither personally inclined towards nor particularly physically prepared for the commission of acts of violence against other persons. I generally think that violence is bad, and am of the strong belief that other reasonably well-adjusted human beings should share my opinion on the matter. This is precisely why I think critiquing liberal pacifism is so important.

I refuse to believe that the comfort of police officers or ICE agents is more important than the safety of immigrants, regardless of the color of their skin or the uniforms on their badges. I refuse to prioritize the survival of cars and walls and windows over the survival of people and families and communities. I refuse to criticize the violence of kids throwing rocks while ignoring the violence of the men in body armor pointing grenade launchers at their heads. I refuse to hand over my fellow protesters to the violence of incarceration or injury or death, even if I find their tactics ill-advised. I refuse to condemn those brave enough to fight back in the face of devastating state violence.

I refuse to content myself with liberal platitudes while a violent system of extraction, incarceration, deportation, and war survives. All power to the rebels of Los Angeles, to those carrying on the tradition of resistance and dignified revolt. May we join them soon.

This post has been syndicated from In Struggle, where it was published under this address.