Like me, you’ve probably been transfixed by the scenes coming out of Syria and especially Sendanya prison. It’s a symbol of everything that was corrupt and cruel and abhorrent about Assad’s regime. An obscene black site for some of the most abominable human rights abuses imaginable. And now the doors are open and sunlight has come flooding in.

I’ve been gripped by the videos on social media in part because in 2019, I went to a talk that changed the way I think about journalism. It was at a conference in Jordon organised by the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism. And it involved Sednaya prison.

What journalists in authoritarian countries know is that you’re never going to be told the truth. The state is going to lie you. So you will have to find other more creative ways to get to the facts. That was the point hammered home in a talk by Shourideh Molavi of Forensic Architecture, a mould-breaking organisation that operates at the intersection of architecture, investigation and human rights. Peppered with fascinating case studies, the story of how Forensic Architecture had attempted to unlock the secrets of Sednaya Prison in a project commissioned by Amnesty International was what gripped me and has stayed with me since.

Amnesty had documented the horrors of the Sednaya “slaughterhouse” – systematic torture, mass hangings, inhuman conditions – but the entire complex was a mystery. The few prisoners who survived or were released told how they were kept in both darkness and silence. But Forensic Architecture decided to interview them and get them to talk about the things they could hear: clanging doors, footsteps, dripping taps, screams. It’s a practice they call “situated testimony” from which architectural and acoustic modellers used these descriptions to map the inside of the prison and break Assad’s black box open.

It was an astonishing piece of work that included an entire 3-D model of the prison and a recreation of the sounds the witnesses heard alongside their testimony mapped into the exact place in the prison where it happened. Even more astonishing was how Forensic Architecture decided it wasn’t journalism or an NGO report and submitted it to the Turner Prize, Britain’s pre-eminent modern art prize. It was an act of great chutzpah. Which worked! It was shortlisted and exhibited at the Tate.

I sat and listened to this in one of those weird conference centres in a luxury hotel in Amman, days before the UK 2019 general election. I hadn’t been to Amman since I’d gadded around Syria in my 20s, living in Beirut in a brief but brilliant moment of post-war optimism. Since then, the Middle East had darkened. But so too had Britain. And I’d found myself caught in the crosshairs of trying to hold Boris Johnson’s Vote Leave government to account, not yet crushed but feeling pretty helpless.

That summer, Nigel Farage’s bankroller, Arron Banks, had issued legal proceedings against me. The police had just dropped their investigations into the illegalities the Observer had uncovered in the Brexit campaign. We’d just published a story about Boris Johnson meeting an ex-KGB officer having left an emergency NATO summit without his security detail following a Russian nerve agent attack on the UK. It had been entirely ignored by the rest of the press. And we were hurtling towards a general election that was going to decide the when, if and how we left Europe forever.

Two things stayed with me: that the kind of journalism we need is the kind that journalists in authoritarian countries know how to do; the kind that works from the outside in; that takes it as read that the state will lie.

And that in the constrained media landscape that we already have in Britan, we need to get creative about how we tell these stories. Johnson’s relationship with a KGB spy did eventually become a scandal but only after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And even now we have no answers, no accountability.

Power is power

Corporate power is not state power but it wears, if not the same clothes, cheap rip-offs. It speaks the same words.And it understands the use of threat. I’ve been writing here and here about the Guardian’s sale of the Observer – an integrated department of the organisation which publishes its journalism online at the Guardian and in a UK print edition on Sunday – and ever since it was announced, we, its journalists, have been pondering the limits of our power.

Our owners, the Scott Trust, entered into an exclusive negotiation with Tortoise Media to secretly sell Britain’s oldest newspaper without its editor even knowing and perhaps the biggest impact of this entire episode is to drive home the weaknesses of journalism.

Despite all the reasons not to, journalists may be some of the last believers in the rules-based order. We live by facts and die by facts and believe facts matter. We may be some of the last inhabitants of a paradigm in which belief in justice, evidence and logic holds fast. We still believe in that old saw that journalism can hold power to account. And maybe one of the most depressing things about last week is what amounted to a crushing philosophical crisis. If journalists can’t do any of those things in their own news organisation, what hope is there in the world outside?

It doesn’t matter that the deal makes no financial sense or that it turns out that the Guardian’s CEO is good mates with the bloke she’s selling it to or that the progressive liberal news organisation we all thought we worked for which has published endless editorials on workers rights, the importance of unions, the labour movement decided to vote for a deal their entire staff protested against…on the day they were actually on strike.

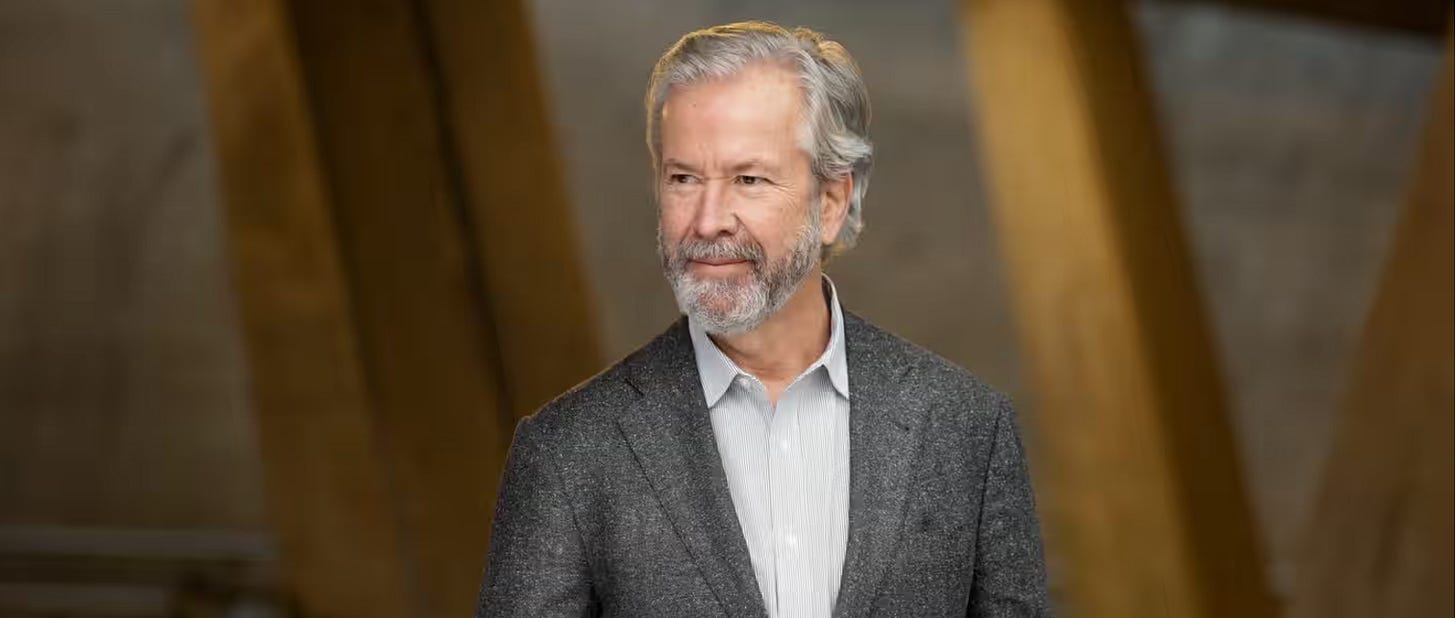

Power is power. The chair of the Scott Trust, Ole Jacob Sunde, the Guardian’s editor-in-chief, Kath Viner, and some other high-profile crash bodies announced it to journalists in a meeting on Friday morning and faced what can only be described as a bloodbath: fury, contempt, disgust. Read about it here and here.

The funniest, bleakest moment came when Simon Hattenstone, one of the Guardian’s best-loved and known interviewers, asked Ole Jacob Sunde if he knew his name. ‘I know your name. What’s my name?’ Simon had been standing outside the building with a loudspeaker wearing a pink hat for the last two days keeping a not very low profile.

Ole said this was a trick question.

On the way out of the meeting, maybe to prove that he did know someone’s name, he stopped to say hello to me.

This was a bit weird. Everyone had left the room apart from a few stragglers. Though in fairness, I’d met Ole in Oslo two years ago when I’d been invited to give a talk by Norwegian PEN. In another life, I’d cast Ole as the silver fox in a Nordic noir, not the murderer but perhaps the father of the troubled-but-brilliant-but-slightly-off-kilter female detective. We see him hanging out in his cabin in the woods making coffee on a simple primus as a drone shot follows her Volvo as it accelerates northwards towards a passionate-yet-contained confrontation.

Or maybe he’s the private banker who takes over a liberal progressive news organisation and sells it to the right-wing mate of his CEO on a deal stitched up on a billionaire’s yacht? What’s confusing is that we thought Norwegians were the good guys. Though some closer inspection of Formue.No, the company Ole founded, reveals a few questions.

‘Money cannot buy happiness,’ the company’s mission statement begins. And goes downhill from there. ‘If more money doesn’t make you happier it’s because you have not yet planned on how you can best utilise it.’

Can no-one buy this man a nice sweater and tell him about journalistic principles?

Turning gold into shit

As luck would have it, I have a question ready for Ole. It’s all I’ve been thinking about for the last five minutes of the meeting which had degenerated into journalists of some 20 years standing shouting ‘Shame’ at the editor-in-chief.

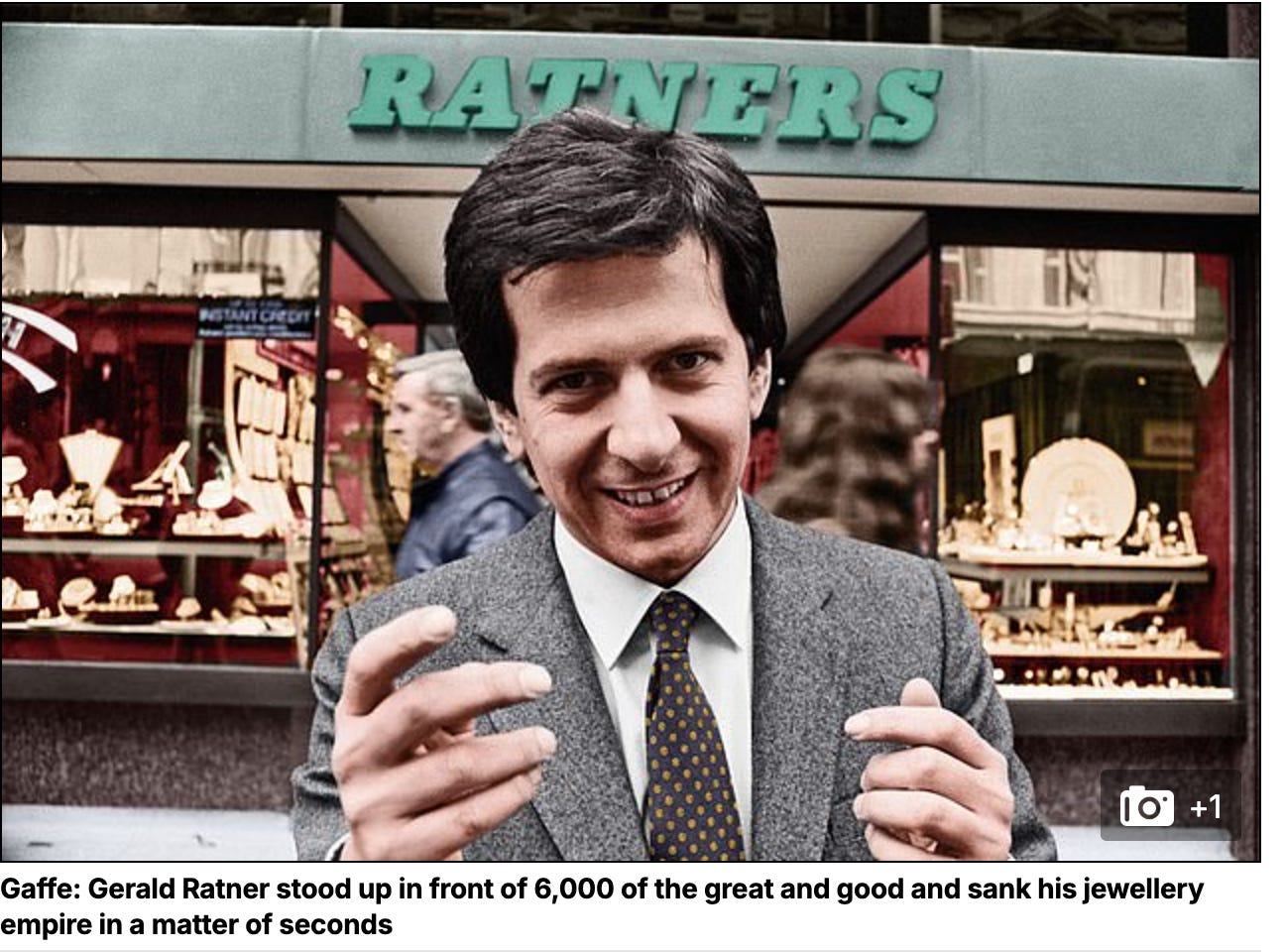

‘Do you who know Gerald Ratner is?’ I ask. Ole shakes his head sadly.

In fairness, the youngsters won’t know either. As I explained to Ole, Gerard Ratner was an 80s businessman who founded a colossally successful jewellery chain that he trashed overnight by treating his customers with contempt when he called his products ‘crap’.

It’s well worth watching the clip. ‘Doing a Ratner’ is now a byword for torpedoing your brand by failing to respect and cherish your customers. If Ole really wants to get up to speed, he could read this Guardian interview with Gerald Ratner by one Simon Hattenstone [but don’t click that link on a strike day, kids.]

The Guardian’s brand has been burnished over decades based on its progressive views on things like workers’ rights, the sense that it puts principles over profits and a workforce of journalists who’ve believed in what they do.

The board and management are obviously pretty sure that this will all blow over soon.

Ole has a cold

My follow-up question was to ask Ole if he’d commit to meet the representative of one of the bidders. He hesitated but said yes, he’d consider any bid.

Shortly afterwards, he gave an interview to a Sunday Times journalist and said:

At 1.29pm on Friday, I followed up by email and asked Ole he’d meet the prospective bidder. He is a credible media entrepreneur with a track record and substantial means, I say, and available to meet on Saturday. Fifty six hours later, I receive a response. Ole says he’d had a cold, hence the slow reply.

The timing was unfortunate. The cold had coincided with the Scott Trust apparently signing (?) an agreement in principle.

In the meantime, the company can’t even get its story straight. The CEO wrote to another set of bidders: “The terms of our exclusivity with Tortoise Media are still in force and so we are not in a position to hold discussions with other potential bidders.”

Wapping 2.0?

I wanted to get this newsletter out at the weekend with joyful snaps of striking journalists but fate had other plans.

But we’re at it again, today and tomorrow. Wish us luck xx

PS: If there’s typos in this newsletter don’t come complaining to me. I never wanted to be out here in Substackland. Write to ole.jacob.sunde@guardian.co.uk.

This is my best attempt to explain the situation so far/aka make myself unemployable on the News Agents podcast.

And here’s one jolly strike pic from back in the days when we thought collective action supported by 93% of the workforce might mean something.

This post has been syndicated from How to Survive the Broligarchy, where it was published under this address.