Last September, I learned via a Sky breaking news alert, that the Guardian was seeking to sell off a core part of the news organisation. My part of it. All of my work has been published on the Guardian’s website – the Cambridge Analytica story actually made more money for the organisation than any other story before or since – but in the UK, it also appears in the Sunday print edition, the Observer.

And on Thursday night 100+ of my colleagues and I were “banged out” of the Guardian’s offices. Yesterday saw the last edition of the Guardian-owned Observer. Tomorrow, after more than three decades as a core part of what is a non-profit organisation, it’s being “transferred” into private ownership.

“Transferred” is corporate-speak for “given away”, if you’re wondering.

My t-shirt is very much not-authorised Guardian merch. It’s based on this message which the website is still using on stories, even now. Which even by marketing industry standards is some next level chutzpah.

A large chunk of the Guardian’s journalism will no longer be “free and open”. It’ll either be non-existent – most of the journalists have no jobs to go to – and those who do will now be published on a privately-owned website behind a paywall.

“Banging out” is a Fleet Street tradition that dates back to the days of hot metal: journalists and printers would “bang” their colleagues out the door when they left, hitting their tools against the metal presses. It’s normally a jolly occasion: a fond farewell to people moving on, to new jobs or into retirement.

This was not a jolly occasion. It was a bloodletting

When the banging actually began, the Guardian newsroom packed into the Observer’s end of the office, it was bizarrely ritualistic, more like a medieval denunciation than a day in the life of a digital media organisation.

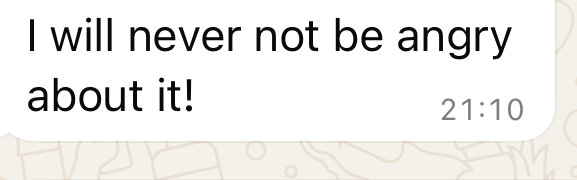

For the last 20 years, my journalistic home has been the Observer New Review. It’s arguably the heart and soul of the paper, home to reviews, reportage, interviews, analysis, culture, politics, tech and much more. And not a single editor is “transferring” across to the new owners. Nor its creative director, its production staff, or its picture editor. They’ve all elected to leave instead. This thread encapsulates just a few highlights of what this this team produced.

I’m genuinely not convinced that the Guardian’s board members are aware, even now, of what they’ve done because I don’t think they ever knew what they had, most are distantly associated with journalism, if at all, based overseas with no grounding at all in newspapers, and this one specifically, the oldest Sunday newspaper in the world. This is living history, one generation bringing on the the next, an oral tradition dating back to 1791.

Great journalism is not just great writing, its great editing, great photography, great art direction, great design, great leadership, great judgment.

This is once-in-a-generation purging of journalist talent. What I’ve so valued and appreciated from my colleagues on the section – especially Jane Ferguson, the editor, and deputy editors, Sarah Donaldson and Ursula Kenny, plus commissioning editors Ian Tucker, Imogen Carter, Lisa O’Kelly and Kathryn Bromwich- is above all their judgment.

When they tell me to re-write or that I need to explain better or that something is in bad taste, or that something just isn’t interesting, I won’t always agree with them, but I’ll always listen to them. There’s something you’ll spot about that team – apart from the brilliant Ian Tucker who’s led on science and tech coverage – it’s a female-dominated, female-led, female-run team. Now blown to the winds.

It’s been a uniquely collaborative and harmonious desk for those who have worked on it and it’s been a dream to write for. I’ve trusted their journalistic instincts and, you’ll have to check in with them, but I believe, they’ve largely trusted mine too.

Over and above everything else, journalism is trust. A compact of trust between readers and editors that social media, in a myriad of cumulative and escalating ways, is breaking down so catastrophically and this whole episode, undertaken in secrecy by an unaccountable and opaque management and board, unnecessarily damages that further.

On the first day of my trial in London’s High Court, I was cross examined under oath by a pugilistic barrister with a strong Belfast accent who made every sentence sound like it was the pre-amble to a punishment beating.

He pulled up one of my stories, published in the Guardian/Observer, and asked me if I took responsibility for the words on the page. “No,” I said. “Miss Cadwalladr, are you telling me that you don’t even take responsibility for your own words?” he thundered, with hammy faux incredulity. No, I said. That article was published four years ago, I have no recollection, now, what I filed, what was changed by a desk editor or a sub-editor. My copy will have been through at least two editors’ hands but more likely more.

Journalism is a team sport, I said.

Journalism is a team sport. It’s why the loss of the Observer New Review team is more than the sum of its parts. And it’s why I should never have been abandoned by the Guardian to face that experience alone – it’s called a ‘trial’ for a reason. I was traumatized by the experience and I use that word in the clinical sense. I haven’t even been able to read the Guardian’s copious daily coverage of the Noel Clarke court case which has just finished. That’s another libel battle that’s being waged against Guardian journalists who are being defended by the same KC in front of the same judge at the same High Court. The difference is the Guardian is paying the millions of pounds in legal fees. It’s assembled a massive team of editors and witnesses. It’s put the weight of the news organisation behind every aspect of the case, the journalists, the witnesses, the defence, the news coverage, the whole thing. It’s made sure the journalists at the centre of it are protected. All of this is as it should be. It’s done the right thing.

But the Guardian will apparently never be able to acknowledge that it did the wrong thing in my case. And, it’s the same management, executive leadership and boards that oversaw and rubberstamped that decision and that have now sanctioned this, another journalistic bloodbath.

It’s not just the New Review, every woman of colour on the paper has also departed. Gone too are the editor and deputy editor of the magazine, both women. In fact, all sections are now edited by men while the Observer editor, Lucy Rock, now shares her job with another woman and reports to a man.

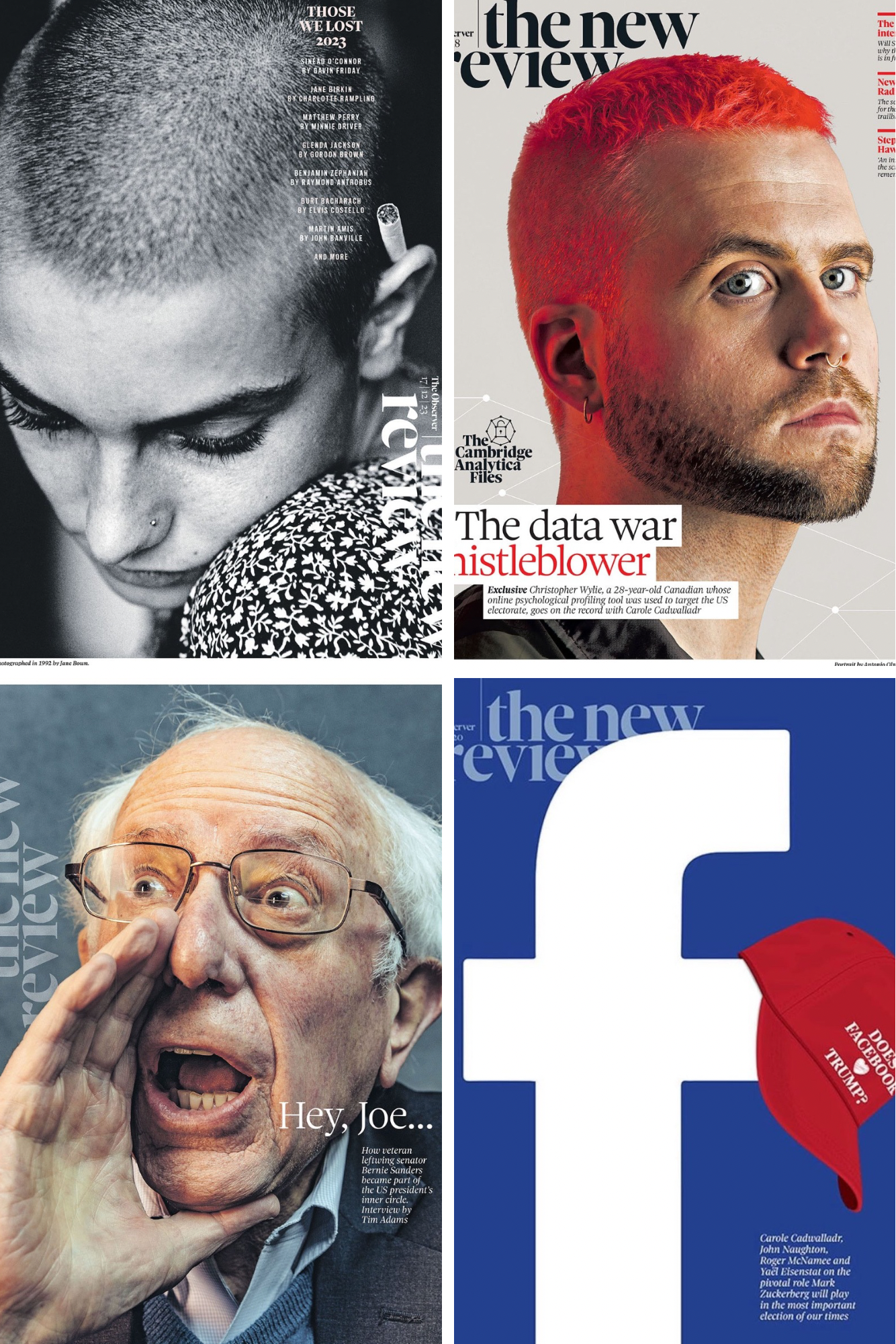

Next week’s Observer will be published by Tortoise Media. Who is Tortoise Media? We still don’t know. Both the Guardian and Tortoise Media refused to disclose its full list of investors and a few weeks ago, Tortoise’s editor and press office declined to answer questions as to whether it has taken Saudi money.

(They did answer the question about the Saudi Media Forum saying they had no idea why the editor was listed as a speaker.)

Tortoise also has some fine journalists. And I wish the small number of colleagues who have “transferred” (we can’t call it a sale because the Guardian actually gave the organisation away with £5m in loose change) the best of British luck. There are some great talents among them and I know that whatever they do they’ll carry the Observer’s history and values with them.

But it’s still a killing. Perpetrated in secrecy by the Guardian and while, there’s been a rearguard action to portray me as some sort of lone troublemaker because I became a media spokesperson during the strike, a fact that’s seen me singled out and punished, I did so speak up on behalf of the 97% of the staff across both titles who collectively disagreed and took the difficult decision to go on strike.

If I wasn’t on what two sets of external legal counsel now say is an illegal employment contract, this would be unfair dismissal.

One day, the definitive piece of what happened will be written about what happened though the question of who can actually write is yet to be determined. My colleagues who are leaving have now been silenced, forced to sign NDAs as part of their leaving deals.

That’s bad practice for any organisation let alone a news one who sees its mission as holding power to account. ITN recently had to abandon its use of NDAs after questions were raised in parliament (women led the way on that one too you won’t be shocked to hear). The only reason I’m able to write this is because I’m not constrained by an NDA because I was offered neither a job nor a pay-off.

Put your head above parapet and there’s a good chance it’ll be blown off. I should know. But as I explained at the time, my loyalty is not to the Guardian’s management or leadership. The Guardian is no longer an independent UK progressive news organisation. It is, for both better and worse, a global media conglomerate.

It’s understandable therefore that it needs execs earning many hundreds of thousands of pounds each but they’ll shuffle off to even more lucrative jobs elsewhere before too long. I had an eye-popping interlude a few years back as a consultant to the Guardian’s executive team after initiating a live journalism strand -TEDxObserver – with then Observer editor, John Mulholland.

It was a compelling insight into the Guardian’s commercial operation that most journalists are kept well away from and which, at the time, seemed both absurd and clueless. It was Mad Men meets Veep with a dash of Enron thrown in. Memorably, we sat through a presentation in which the membership team’s in-house Pete Campbell pitched the idea of corporates paying big money to have dinner with Guardian columnists. Or what we journalists call “cash-for-access”.

But the other lesson, is that, unlike the journalists and the readers, none of people involved are there are any more. At some stage, Google or Unilever will offer the people who cooked this idea up more money and they’ll push off back to where they came from.

It’s the readers and journalists who are in it for the long haul. We were there before they arrived and we should be there after they’ve gone. That we’re not is simply a bullet point on their CV, a cost saving on a bottom line, not a broken promise or a cultural wrecking ball. They will not live with the consequences.

The editor-in-chief’s role in all this is a subject for another day.

All of which is a long way of saying je ne regrette rien. I dedicated my TED talk last week to the 30,000+ readers who supported me through that trial who weren’t consulted about the Observer’s future or even informed. Most are still completely in the dark. To those who’ve followed me here, an even more heartfelt thanks.

Talking TED

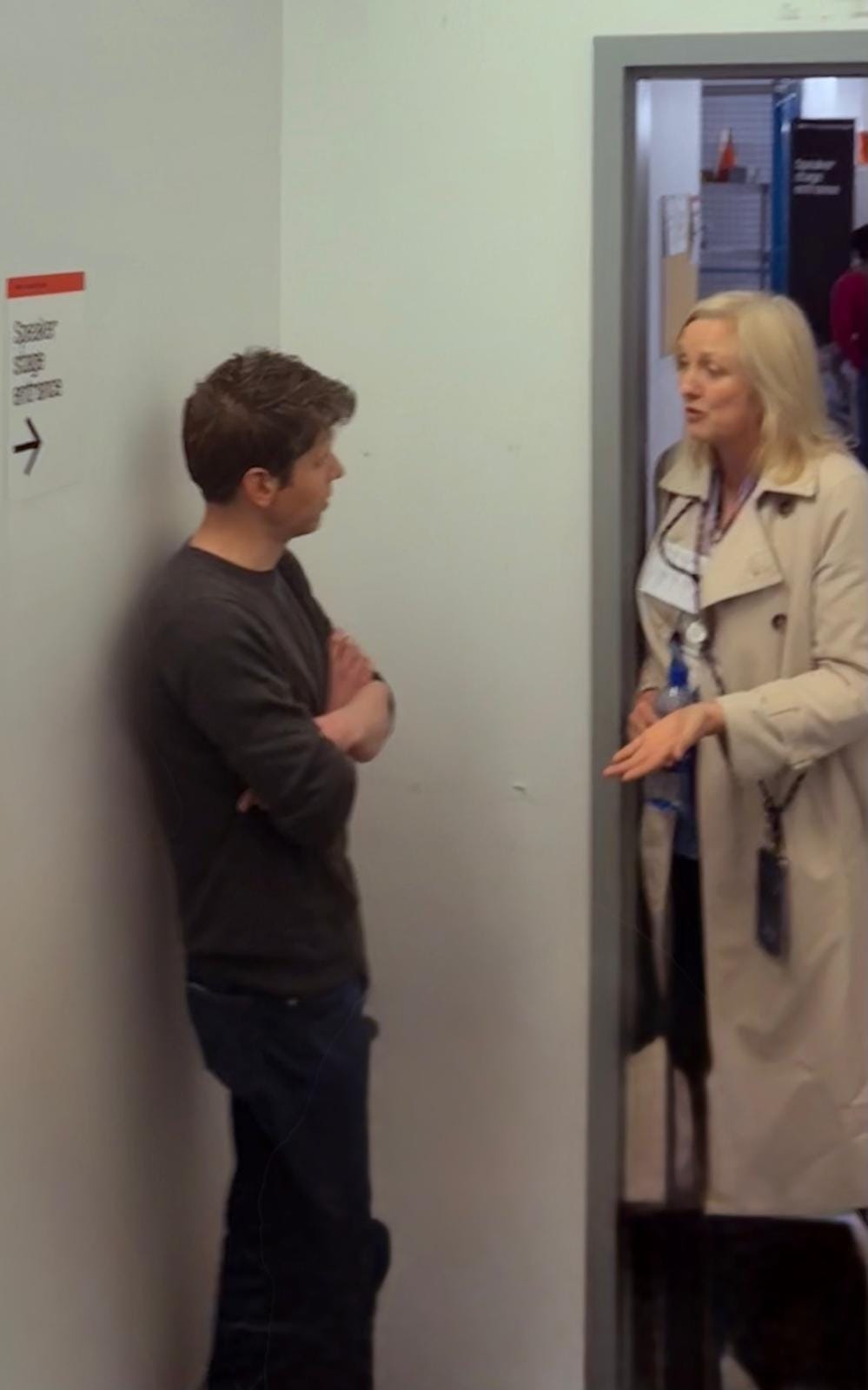

I have so much to say about the experience of being at TED, giving that talk – here on YouTube This is What a Digital Coup Looks Like – and also the response to it. Sometime in the last 24 hours, it passed the one million views mark on YouTube and Brian Greene, TED’s director of publishing, keeps sending me fascinating stats, including that it’s the most viewed TED talk of the year and it’s attracted an extraordinary 3,900 comments.

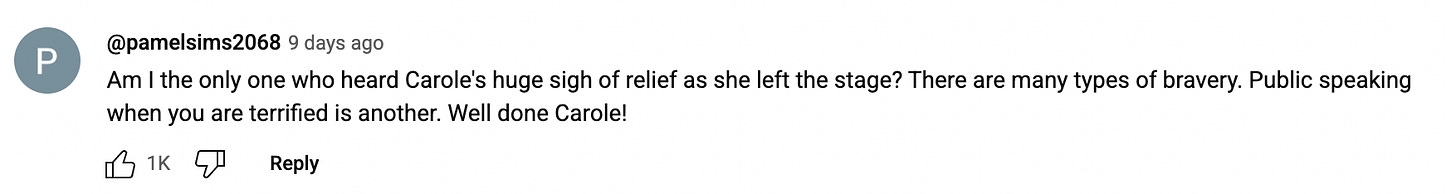

There’s a bit more background on TEDtalks Daily, TED’s flagship podcast where the head of TED, Chris Anderson, challenged me on what I said about Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI and then interviewed him on the main stage where he put my points directly to him.

I actually got to meet Altman afterwards. Here we are, backstage, chit-chatting about ChatGPT and data rape. More on that in the next few weeks.

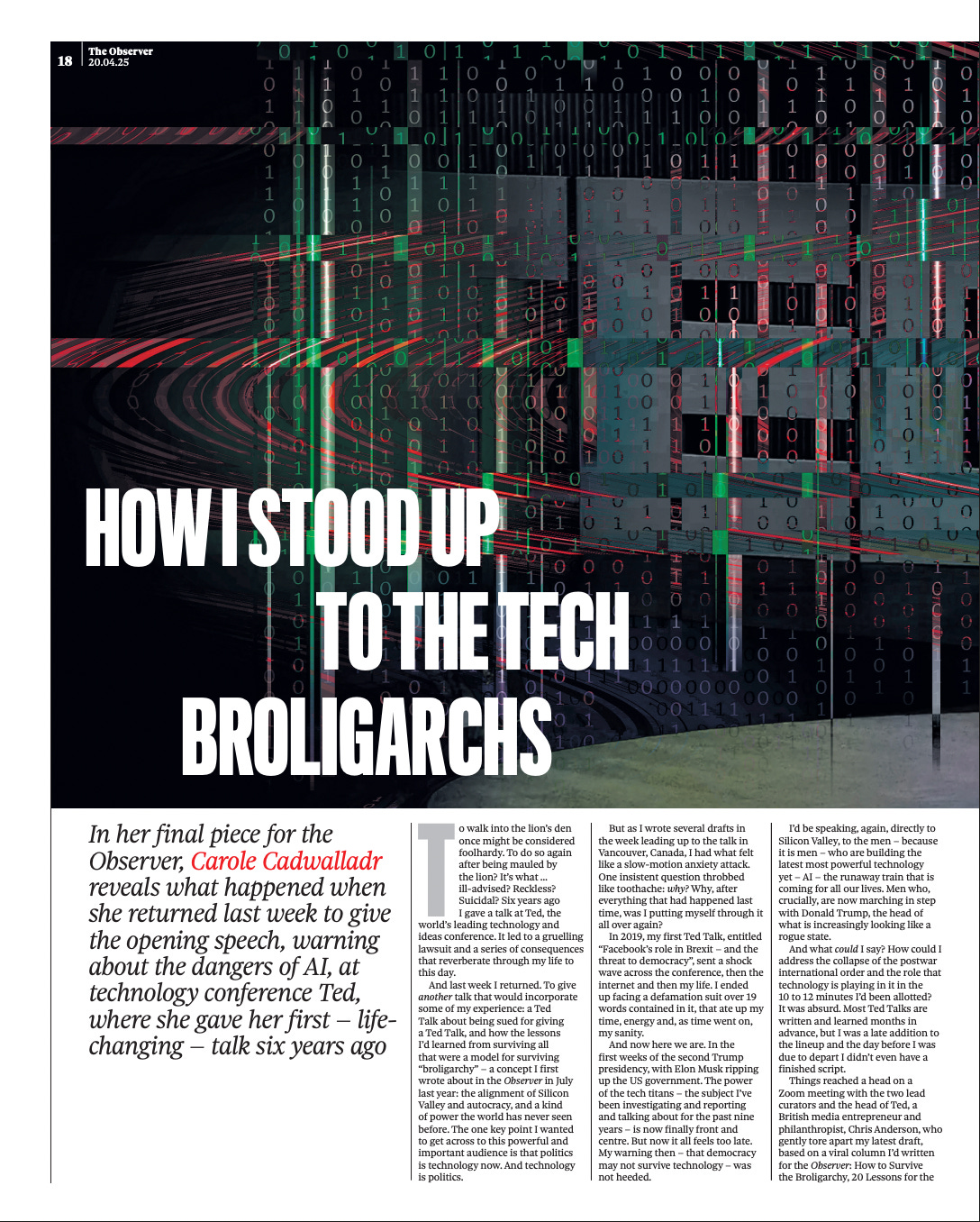

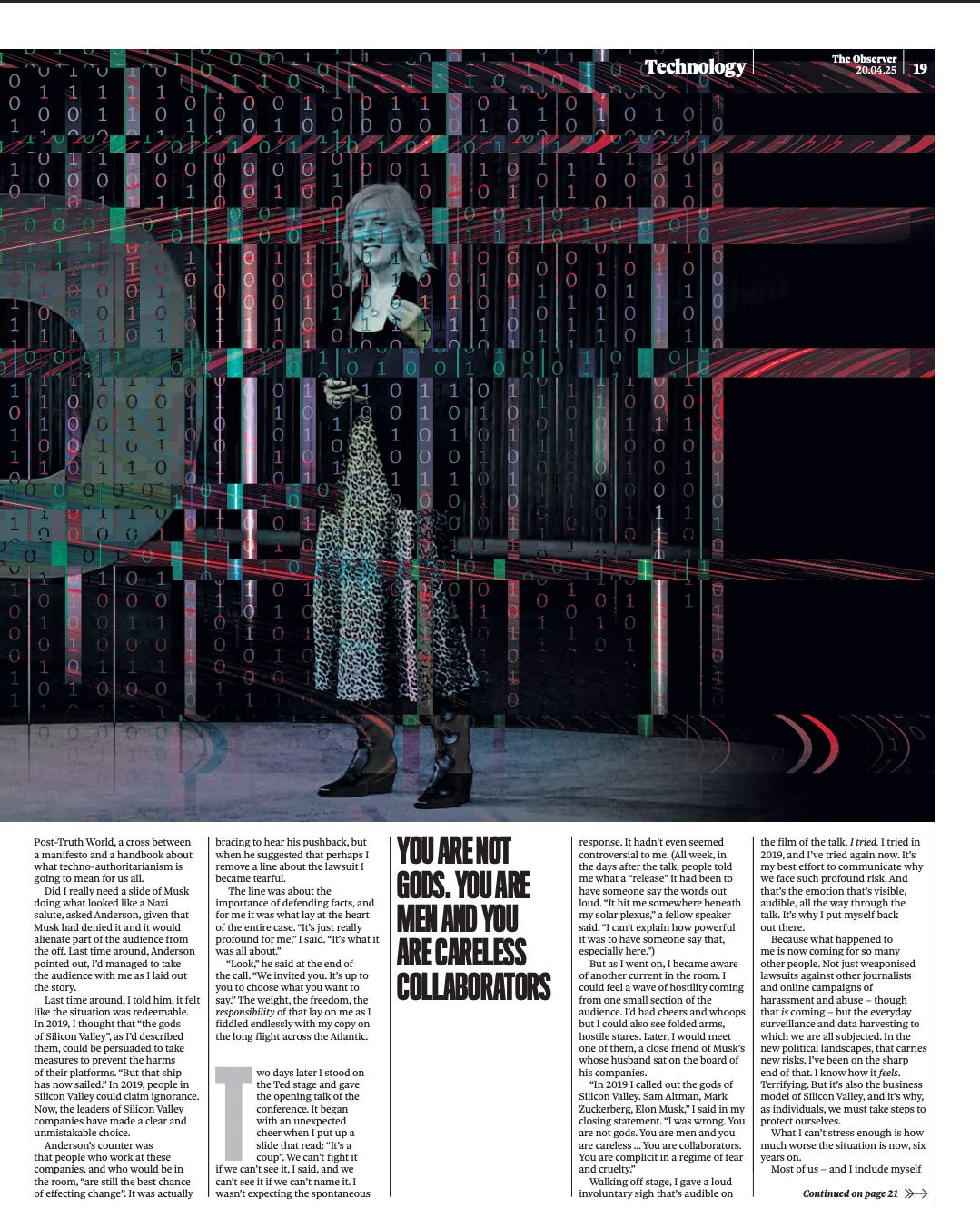

I also managed to write about some of this experience in the last ever edition of the Guardian-Observer. Thank you, as ever to my New Review colleagues, for including me in their last ever section:

The missing photo

Here’s a pic of one moment of the talk that was left off the Observer New Review spread:

Endings and beginnings

I love a good story and I couldn’t have scripted a weirder ending to this chapter of my life. TED talks but as directed by David Lynch.

Thank you TED for having me. To the curation team: Helen Walters, Cyndi Stivers and the head of TED, Chris Anderson, especially. It felt like a massive risk and a gamble for all of us, and may yet still be.

Anyway. Happy Easter, from death comes life and from the entwined global political and media crises will come new journalistic innovation, new ways of confronting power. I believe the darkening storm in the US will create an equal and opposite force that will push back against it. And that has to also include Silicon Valley. Please do sign up for the Citizens Dispatch, which is bringing together the voices who are trying to do just that.

What’s so odd is that I feel calmer now than I have for a long time. The threat is finally visible. It’s honestly a relief. It took Elon Musk to take an axe to the US government but the threat from vast data harvesting tech monopolies is finally fully out in the open. I, along with so many other people, have felt gaslit and marginalised, for insistently sounding an alarm that much of the mainstream media and politicians have refused to hear.

It’s a line in the sand for me, in many ways. And I want to try and think carefully about the next stage forward. And I’m hugely grateful to everyone who’s reading this and especially subscribing to it for enabling me to be truly independent. It’s scary but liberating. Apologies to anyone who’s been trying to get hold of me in the last couple of weeks. It’s been a maelstrom but I’m so happy to be here with you for the journey into the great unknown. With massive thanks, Carole

PS If you’re not familiar with the reference “Fuckity bye” is the sign-off of the great Malcolm Tucker, star of The Thick of It by the brilliant Armando Iannucci who created Veep so there’s a thread of connection right there. I stumbled on this clip of Tucker visiting the Guardian while searching for it. Enjoy!

PPS If you’re terrified of public speaking, it really is worth trying to get over it, especially if you’re a woman. I refused for decades to speak in public let alone on a stage in front of more than 1,000 people with no notes. A debt of thanks to Sarah Quist, an actor who coached me last time around. This time around, I hadn’t even finished writing the talk by the time I got to Vancouver but she patiently sat on the end of several zoom calls and kept telling me not to worry that I didn’t know it word for word. “It is within you,” she kept on saying. Most of what she taught me was how to stand tall, not be intimidated and to speak directly to people who don’t necessarily want to hear what I have to say; lessons for life. Thank you, Sarah xx

This post has been syndicated from How to Survive the Broligarchy, where it was published under this address.