Resistance is something alive or it is nothing at all. We can trace back the lineages of our resistance through the generations of militants and martyrs, witnessing the path blazed by the torch we carry today. But that history must connect to the contradictions and struggles confronting us today, here, now, or else it’s just a historical curiosity.

This is the meaning of revolutionary tradition: not a parade of icons or compendium of slogans but the understanding that past struggles might orient us within the ones we find ourselves today.

Why, then, is the introduction to anarchism so often haunted by ghosts?

Perhaps we learn first that anarchy means something other than chaos and disorder. We then become acquainted with the shocking fact that revolutionary anarchism was once a mass movement of millions, that stateless socialism was the main thrust of revolutionary workers’ movements before the October Revolution. We might then learn that anarchism is alive today, in street medic collectives and saboteurs, labor organizing and leftist study circles, DIY biohacking and distributing Narcan and food.

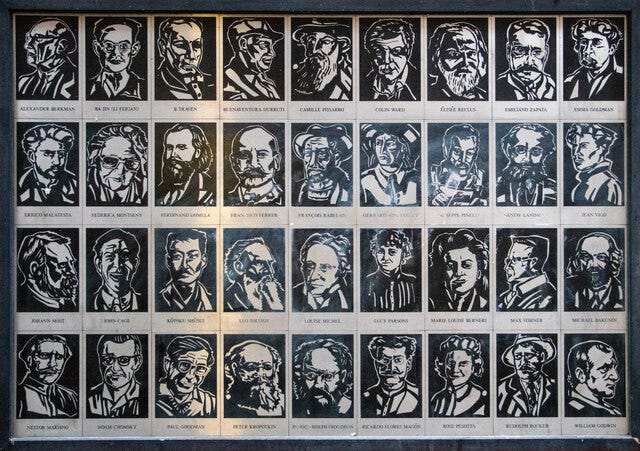

But then, at some point, we are told we must become acquainted with a succession of ghosts. The Emma Goldmans and Mikhail Bakunins, the Kropotkins and Proudhons, the siren songs of revolutions defeated. Their names are kept alive as subcultural lore, because Western anarchism has been kept alive predominantly through white punk subcultures.

I’m not saying you shouldn’t read Emma Goldman if you want to read Emma Goldman. I mean, I would recommend it; she had some real bangers. But when Red Emma was scaring cops and politicians shitless in early 20th century America, she was doing so as a dispossessed ethnic minority immigrant labor organizer who eventually got deported for it. And dispossessed ethnic minority groups are kind of the exact opposite of majority-white subcultures.

What I’m saying is that if white punk bros are the Exclusive Experts in Anti-Authoritarian Socialism, we will absolutely never win. I mean, no offense or anything, but the whole point of a subculture is that it’s, to some degree, exclusive. Hidden. Underground. A refuge from hegemonic culture, but something that can’t become hegemonic culture. This is important because societal transformation requires building a bloc of a whole buncha folks. Maybe not most, certainly not all, but a significant plurality of people. This isn’t all that crazy; in the summer of 2020, a vocal plurality of white Americans, of all people, decided abolishing the police would be a-OK. But if a precondition for joining this bloc is personally enjoying Crass or Napalm Death records… well, in that case we’re kinda fucked.

Again, no offense intended. I’m not saying we should cancel anarcho-punk or anything. Again, it’s the reason why anarchism has survived as an idea in many places to the current day, and I think places that connect us with revolutionary tradition are valuable and precious. But if we’re looking to transform society, I think we need to start looking for anarchism in action in unexpected places.

For one thing, it might be called something else. A lot of people have adopted the framework of abolitionism, which, I would argue, is 1000% the same thing as anarchism, although perhaps with less baggage. But even beyond that, what if we looked for the seeds of anarchic practice in the same ground it’s always flourished: in oppressed communities.

William C. Anderson and Zoé Samudzi have written about Black America as “an inherently anarchistic element of the United States” since “assertions of Black personhood, humanity and liberation have necessarily called into question both the foundations and legitimacy of the American state.” Today, we have oppressed immigrant communities exploited at sweatshop jobs, though they aren’t the Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews of Emma Goldman’s day. Some of them hail from the areas of the world with the richest contemporary anarchist and abolitionist traditions: sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.

In my book Defying Displacement, I argue that oppressed communities that are skeptical of political representation, fighting capitalist exploitation, and struggling for survival and self-determination might not be anarchist but are certainly doing anarchism. This is what I call the “anarchism of praxis,” a practical anarchism that’s not reflected in doctrinaire ideologies and subcultural norms. Its protagonists might describe their beliefs in any number of ways. It grows out of, not waits to be extended to, the “inherently anarchistic element” of those who are displaced first: the Black, Indigenous, and immigrant communities already “residents in” and not “citizens of” the United States. The anarchism of praxis is the practice of survival for those targeted for removal by capital and the state.

This is our task: to notice the seeds of abolitionist practice, to nourish their growth, to cohere a revolutionary bloc to effect the transformative change our communities, our neighbors, and our planet need to survive and flourish. Let’s leave the old gods where they lay; we are pulling the horizon of liberation closer.

This post has been syndicated from In Struggle, where it was published under this address.