Standing in the parking lot of the El Portal Church of Christ in the Richmond, California area, unhoused people are quick to give O’Neill Fernandez a hug—or just chat. Some have come to shower in a mobile unit run by his employer, Safe Organized Spaces Richmond, better known as SOS. Fernandez was in their shoes, living in a tent with his pregnant wife and struggling with drug addiction when he began volunteering to pick up trash with the nonprofit’s street team: it was better than “sitting in a tent all day,” Fernandez said. Today, sober, he’s SOS Richmond’s director of wellness and programs.

“Ultimately, we know how it feels,” Fernandez said. “How can people [say] ‘this is good for someone’ when they haven’t walked the walk?”

Encampments in the San Francisco Bay Area have been growing for decades, closely tracking rent increases that have driven many families out of their homes. Officially, there are close to 40,000 unhoused people in the region, a likely undercount. Unhoused people face intense policing, with their medicine, clothes, and mementoes being seized in sweeps that have only grown since a June 2024 Supreme Court decision in favor of such measures—which can temporarily remove people from the streets, but rarely get anyone housed.

“How can people [say] ‘this is good for someone’ when they haven’t walked the walk?”

Encampments are often left out of city services like garbage disposal, and the build-up contributes to their public image as waste-filled places where nothing good happens. The so-called “tough love” approach of California Gov. Gavin Newsom, who recently called on California cities to ban homeless encampments, as well as many local mayors—has often focused on visuals of trash, in Newsom’s case including a photo op where the governor appeared to remove someone’s belongings in a shopping cart.

SOS Richmond’s founder, Daniel Barth, told me he got a spark to start the organization in 2018 while helping protect an unhoused man’s belongings from “abatement”—a euphemism for city workers hauling out people’s belongings, often directly to the dump. The man asked how he could get a similar job: in their place, he’d know the difference between actual waste and the only valuables a person may have.

Barth wanted to start an organization that recognized the people living in encampments in and around California’s increasingly unaffordable cities as parts of those communities—one that would work to minimize hostile interactions with police and city workers, facilitate long-term, stable housing, and pay people to clean encampments humanely. Around 80 percent of SOS’ roughly 30 staff are currently or formerly unhoused. In their entry-level positions, staff work about 18 hours a week to meet the needs of other unhoused people and pick up around 25 tons of trash a month. For some, it’s a stepping stone to other careers.

Despite the region’s massive influx of tech-industry funds, Richmond is still a working-class town; its average household income of around $100,000 is about two-thirds the Bay Area norm. It’s also heavily Democratic—but the city council is rife with arguments about how, and how much, to spend on the housing crisis. Last fiscal year, about three percent of the city’s $250 million operating budget went to supporting unhoused locals. Richmond’s progressive mayor, Eduardo Martinez, a former teacher, ran in part on affordable housing, pushing against subsidies for luxury housing supported by Chevron, the city’s biggest employer.

Money alone hasn’t always helped. Many well-funded initiatives to address the Bay Area’s housing crisis have fallen short—including, as a 2024 Urban Institute report found, that of Levi Strauss heir (and now San Francisco mayor) Daniel Lurie. By its own count, Lurie’s $100 million Tipping Point Community project allowed San Francisco to move about 700 people out of chronic homelessness—a third to half as many as it aimed to, in part due to shortcomings in collaboration with local governments and limitations in addressing the roots of homelessness.

The voices of Silicon Valley tend to dominate homelessness response in the Bay Area, says Lukas Illa, an organizer with the Coalition on Homelessness. What’s more important, Illa believes, are measures like San Francisco’s Proposition C, a 2018 tax on large businesses to fund homelessness services—which they doubt would have passed if tech billionaire and political heavyweight Marc Benioff hadn’t broken ranks with fellow billionaires opposing it, including Twitter founder Jack Dorsey and Stripe CEO Patrick Collison. “It was a huge win,” Illa said. “I wish the testimony of the lived experience of people on the streets was enough for the voters to understand that.”

For around four years, SOS has maintained a formal, ongoing relationship with the city of Richmond, with the organization’s staff fielding presentations on their work at city council meetings and SOS’ O’Neill Fernandez becoming a member of the city’s Human Rights and Human Relations Commission. The support of the city, and the surrounding Contra Costa County, gives SOS a role in everything from health services to more fundamental questions of housing supply.

“If you have somewhat of a cooperative environment, where the moderates and the progressives are working together,” Barth said, “then you can get positive movement.”

If the city gives SOS notice, for instance, that it plans to move RVs parked on Richmond city streets, then the organization will step in to help. “If that vehicle can’t move, we’ll move it for them,” Barth said. “We won’t tell them where to go; they will tell us where they want to go, and then we’ll go.”

Relations were not as smooth with Richmond’s last mayor, Tom Butt, who wasn’t convinced that people needed support beyond housing grants to keep them from eventually returning to the streets; Butt also, during a disagreement with progressive council members, encouraged unhoused people to camp outside his opponents’ homes. SOS partners with other groups to maintain contact even once people are housed; I spoke to SOS care team coach Terro McMillion, who told me that, although he’s now been housed for months, a volunteer still calls him weekly to see how he’s doing.

After spending some time at SOS’ headquarters in Richmond and at the shower station, I went with Fernandez and Barth to the San Pablo Creek encampment, which is around two decades old and home to about 230 people. Fernandez knows it well: he lived here twice, the first time for a few years beginning in the late 2000s.

Waste at the encampment is best described as an organized mess. Residents place it in piles, knowing that SOS’ workers will come by to pick it up. Others I spoke to told me that they took advantage of the showers the group offers twice weekly.

SOS’ ability to help its residents speaks to the importance of nonprofits where cities can’t step in, Suffolk University professor Saerim Kim told me. Independent groups are more able to operate between jurisdictions, says Kim, whereas local governments “have a lot of bureaucratic restrictions” that nonprofits aren’t stifled by.

Between conversations with the encampment’s residents, Fernandez was taking phone calls to help coordinate care. “A big portion of my day,” he says, “is also putting out the fires that happen”—like issues at hotels where SOS is helping people transition to conventional housing. Often, he says, the calls start coming in early in the morning, while he’s spending time with his child.

One resident, Mike, told me that he’d been living in the encampment for four months; he has two pitbulls, one of which was licking his face throughout our conversation, and lives with paranoid schizophrenia. “Been better here than anywhere else in the county,” Mike said, “because the cops really don’t come to mess with us.” He credits SOS’ close involvement.

After the murder of George Floyd, the Richmond City Council established a committee to reimagine public safety, and in 2021 voted to redirect millions of dollars from the Richmond Police Department’s $72 million budget to community resources like SOS. The shift was not influenced by tech industry leaders—although SOS has received some support from Chevron, which operates a refinery in Richmond and has come under pressure to mitigate its detrimental climate and health impacts. “We have to be willing to continue to make bold changes,” then-vice mayor Melvin Willis said at the time; more than a year later, Willis stood by the move and remarked that he was proud of SOS’ rapid growth.

“Crisis is what throws them off the normal trajectory that most of us have.”

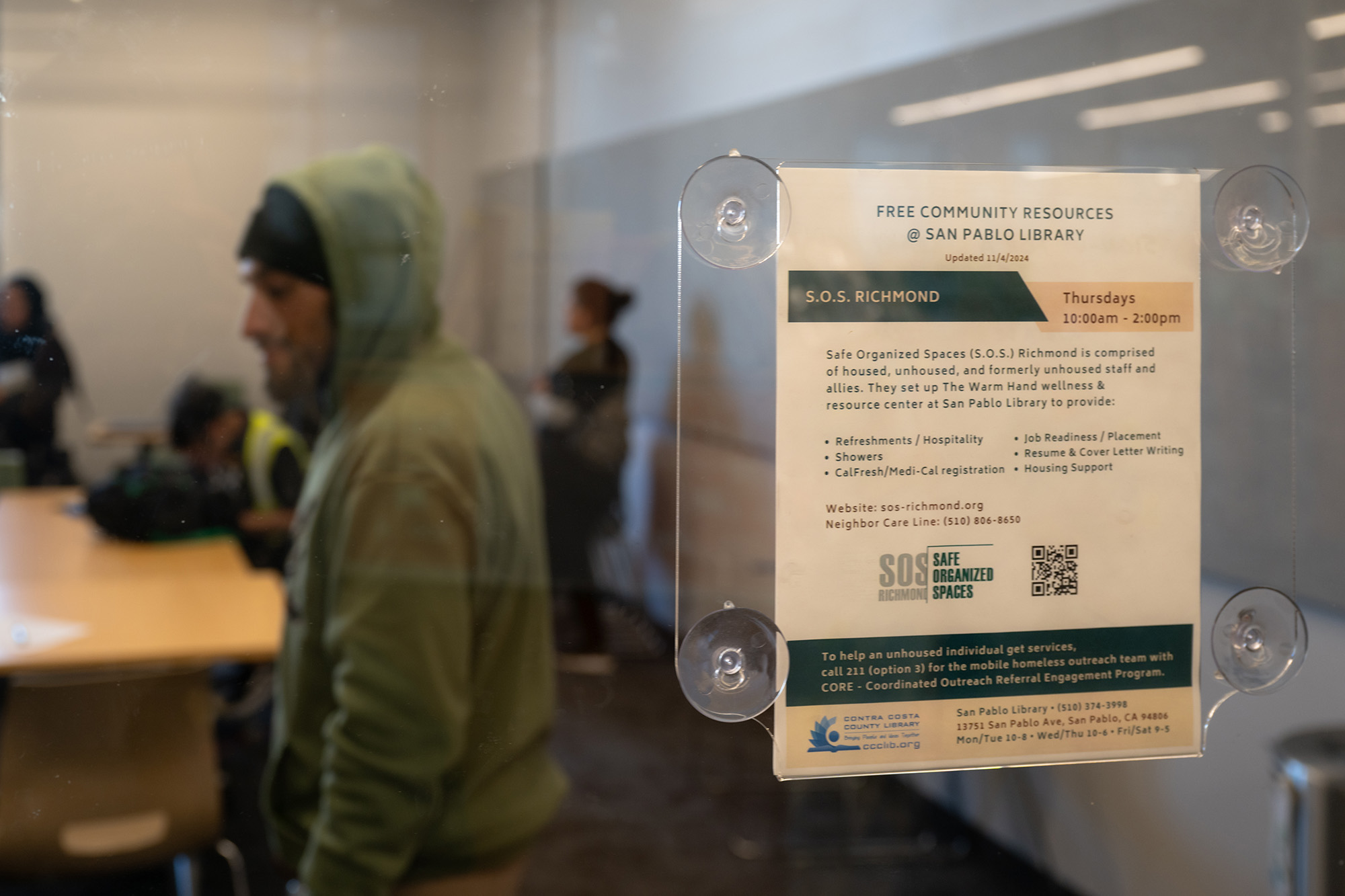

At the group’s wellness pop-up at a local library in the neighboring San Pablo, I ran into Vicki Danley, a social worker with the county’s behavioral health services program, who was dropping off clothes for SOS to provide. Danley said she referred four or five people a week to the group for support, and vice versa—SOS Richmond encourages the people it works with to seek out county workers like Danley to help coordinate mental health services.

At the library, I also met SOS workforce manager Janny Castillo, who helps with SOS’ 60-day readiness program, which mixes around six hours of job training coursework with 10 to 15 hours weekly of paid work for SOS; most who go through it continue to work for the organization. Castillo herself experienced homelessness for nine years as a mother; she’s known Barth for more than 20, since a stretch working together at a homeless shelter. Most people Castillo works with already have regular work experience, she says, and “crisis is what throws them off of the normal trajectory that most of us have.” (Fernandez, for instance, worked as a cook while homeless.)

She finds that people have more hope for the future when they start jobs through the organization; challenges like navigating job applications with a criminal record and explaining gaps in employment are a case study in the need for supportive services beyond housing. “I don’t have to go commit crimes to make money,” said Marcela Hidalgo, a street team member.

SOS Richmond, and organizations like it, acknowledge that they won’t solve the homelessness crisis alone, nor do they seek to—nor can any small (or even large) nonprofit. But what makes it unique, says Castillo, who has worked with other homelessness-focused nonprofits, is that in mainly employing unhoused people, it is “deeply rooted” in a foundational effort “to be peers and to be partners and to be equals.”

This post has been syndicated from Mother Jones, where it was published under this address.