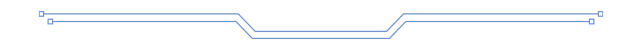

Early last year, a group of entrepreneurs and tech enthusiasts from around the world gathered inside a newly built dome on the Honduran island of Roatán to grapple with a problem: For thought leaders who want to move fast and break things, what can be done about laws that get in the way? The conference, sponsored by the Salt Lake City–based Startup Societies Foundation, was being put on in Vitalia, a longevity-themed “pop-up city” that caters to American medical tourists sidestepping cumbersome FDA regulations. Its motto: “We’re here to make death optional.” Vitalia was in turn located in Próspera, a semiautonomous city on Roatán. Imagine a nesting doll, a city within a city within a city—all on a Caribbean isle.

Próspera, the project of entrepreneurs funded by venture capital firms backed by PayPal founder Peter Thiel and venture capital mogul Marc Andreessen, was established in 2017 and continues today, despite repeated efforts from Honduras to shut it down. An example of a “special economic zone,” Próspera is an autonomous jurisdiction with limited regulations. The general idea has been around for years—Mother Jones wrote about a failed Thiel-backed effort to build floating cities at sea back in 2012, for example. But in recent years, Silicon Valley founders, as they like to call themselves, have reworked the concept into the “network state,” as coined by entrepreneur and investor Balaji Srinivasan, a close friend of Thiel’s and a former colleague of Andreessen’s. As journalist Gil Durán observed in a New Republic piece on Srinivasan last year, “Balaji’s politics have become even more stridently authoritarian and extremist, yet he remains a celebrated figure in key circles,” including multiple Signal chats that, Semafor reported in April, helped radicalize the Silicon Valley elite.

In a 2021 essay on his website, Srinivasan laid out his vision for people seeking to build a new utopia or, as he put it, “a fresh start.” Sure, there were conventional ways to do this—forming a new country through revolution or war. But that would be, well, really hard, not to mention unpredictable. A cruise ship or somewhere in space were appealing options, but both presented logistical challenges. Far simpler and more practical was “tech Zionism,” creating an online nation, complete with its own culture, economy, tax structure, and, of course, startup-friendly laws.

Eventually, Srinivasan mused, such a community could acquire actual physical property where people would gather and live under the laws dreamed up by the founders—a “reverse diaspora,” he called it—but that land didn’t even need to be contiguous. “A community that forms first on the internet, builds a culture online,” he said, “and only then comes together in person to build dwellings and structures.” Acknowledging that the idea might sound a little goofy—like live-action Minecraft—he emphasized that it was also a serious proposition. “Once we remember that Facebook has 3B users, Twitter has 300M, and many individual influencers”—himself included—“have more than 1M followers,” he wrote, “it starts to be not too crazy to imagine we can build a 1-10M person social network with a genuine sense of national consciousness, an integrated cryptocurrency, and a plan to crowdfund many pieces of territory around the world.”

A network state would, like a kind of Pac-Man, gobble up little pieces of actual land, eventually amassing so much economic power that other nations would be forced to recognize it. Once that happens, laws in more conventional nations could become almost irrelevant. Why on earth would, say, a pharmaceutical company with a new drug choose to spend billions of dollars and decades on mandated testing when it could go to a deregulated network state and take it to market in record time? As Srinivasan argued in a Zoom talk at last year’s conference, “Just like it was easier to start bitcoin and then to reform the Fed,” he said, “it is literally easier to start a new country than to reform the FDA.”

Srinivasan’s post and a follow-up 2022 book, The Network State: How to Start a New Country, quickly gained a robust following; the week it published, it was No. 4 on the Wall Street Journal nonfiction bestseller list. In 2023, Ali Breland wrote for Mother Jones about Praxis, a “cryptocity” concept that drew tens of millions of dollars in investment from Srinivasan, Thiel, Palantir co-founder Joe Lonsdale, and other Silicon Valley heavyweights. While its promised physical city has yet to materialize, Srinivasan has produced two annual Network State conferences, as well as the Network School, a training program for aspiring nation founders located on an undisclosed island near Singapore.

Srinivasan isn’t alone in envisioning these utopias. New projects with ideas similar to the network state are popping up all over the world. Srinivasan’s friend Andreessen is a key backer of California Forever, an effort by a group of tech billionaires to turn part of the San Francisco Bay Area wine country into a new city with a “dedicated Industry & Technology Zone.” In Africa, a Srinivasan-funded initiative called Afropolitan aims to create a digital state for entrepreneurs. Crecimiento wants to make Argentina the “world’s first crypto nation.” Saudi Arabia is in the process of creating an $8.8 trillion special economic zone, flattening Indigenous villages in the process.

At the Roatán conference, participants excited about making Srinivasan-style special economic zones in the US complained about stringent city laws that stood in the way. During a Q&A following a talk by Lonsdale, an audience member wondered whether partnering with “jurisdictions that have equivalent and arguably even higher status, like federally recognized tribes,” might present a workaround. Lonsdale agreed. He had just spoken with someone from the Chickasaw Nation. “I think people at the federal level on the right are very open to these types of things,” he said. “We should probably get Elon to help us build the infrastructure for some Indians.”

If Elon Musk did want to follow up with “some Indians,” he wouldn’t have to start from scratch, because a tech-backed carveout of Native territory already exists—and it’s a good example of the speed at which Srinivasan’s vision is becoming reality. In 2022, the Catawba Nation, a tribe of about 3,000 people with land in both North and South Carolina, launched America’s first “Digital Economic Zone” where entrepreneurs can incorporate online companies—especially banks—without the burden of “archaic paperwork and in-person documentation,” the website says. “Today, we are taking a progressive step into the digital age by leveraging our tribal sovereignty in innovative ways for the benefit of the web3 industry and our people.”

The Catawba DEZ (or CDEZ) is a radical new offering in what its backers conceive of as a kind of free market of governments. Instead of figuring out how to establish a business that abides by existing laws, entrepreneurs can shop around to figure out which deregulated zones have the laws (or lack thereof) that best suit their businesses. “Traditionally, that has been done physically. You usually set up an office or some sort of a physical building within that zone,” Joseph McKinney, CEO of CDEZ, explained in a 2022 interview. “But with the zone that the Catawba are building here, what [entrepreneurs] need to do is register virtually to set up a company.”

McKinney has not said he is a member of the Catawba tribe, nor has he indicated that he is Native American at all. Before founding CDEZ, he worked for a now-defunct consultancy that advised countries on establishing special economic zones; he also set up the Startup Societies Foundation, the group that sponsored the conference on Roatán.

Through Chapman University law professor Tom W. Bell, author of a 2017 book called Your Next Government? From the Nation State to Stateless Nations, he heard that the Catawba tribe might be interested in setting up a special economic zone. In a 2024 appearance on a Brazilian podcast, he recalled his initial skepticism and how he falsely believed tribes “don’t have real sovereignty, that they’re paper tigers.” He was pleased to discover that Native American nations “have at least the same regulatory and legislative authority as a US state regarding commercial law, corporate law, and business regulations.”

So McKinney and his wife—Nathalie Mezza-Garcia, a political science and government PhD who founded a consulting firm for floating special economic zones—decided to settle near the Catawba Nation and set about “meeting with tribal elders and heads of families…at all-you-can-eat buffets and coffee shops” to pitch their plan. In February 2022, the tribal legislature voted to officially create the Catawba Digital Economic Zone.

That McKinney, who didn’t respond to an interview request, was able to make this happen is impressive to Patri Friedman, grandson of conservative economist Milton Friedman and founder of Pronomos Capital, a startup societies investment firm. A Thiel acolyte who has invested in Próspera and a nonprofit that aims to create floating cities at sea, Friedman told me that people in the network state movement had been “suggesting doing something on Native lands for 25 years.” We met at a gathering of pronatalists, a coalition of religious fundamentalists and eugenics-curious techies who want Americans to have more babies. “You have to find the right tribe that has the right mindset and build a strong relationship with them,” he said. “I think that’s the hardest part. Joe, he’s the only one who’s been able to pull that off.”

With CDEZ up and running, entrepreneurs can register their companies there and enjoy lower fees and taxes and less regulation than is available even in notoriously corporate-friendly states like Delaware and Wyoming. The Catawba Nation’s right to operate under its own civil code “protects the autonomy of the Nation’s legal system from the judgments of state or federal courts,” Chapman University’s Bell wrote in a 2022 paper about CDEZ. Physical expansion was possible as well. “The beautiful thing about tribal nations, and the Catawba specifically, is that you can put additional land into their jurisdiction through an established process,” McKinney has said. Off the reservation, he noted, there are “property owners that actually own very large factory buildings and manufacturing facilities that actually want to put some of that land into [tribal] trust to build an industrial park or what have you.”

CDEZ has promised that Catawba tribal members will enjoy “unprecedented career and job opportunities” and “economic opportunities that did not exist prior” to its creation. But what exactly are those opportunities? For tribal citizens who want to incorporate, CDEZ waives the annual renewal fees of $100. In an email to Mother Jones, Scott Charles, a Catawba citizen who serves as a CDEZ commissioner, noted that its roster of 121 businesses includes seven owned by Catawba citizens—among them a ballistics manufacturer and a communication and security platform for tribes. More substantially, the tribe is the official owner of CDEZ. Charles declined to say how much revenue has been generated and instead highlighted plans he said were in the works to provide free consulting and tech support to Catawba entrepreneurs, as well as a preferential hiring program that could bring “higher wages, employment training programs for tribal citizens, business contracts for tribal-owned companies, technology transfers, and further infrastructure improvements on tribal lands.” The tribe has also set aside half a square mile of land for commercial development that it hopes will generate tax revenue.

In an August 2024 Instagram post, CDEZ boasted that the zone “leads in legal innovation” and is “[paving] the way for the future.” The company doesn’t identify those enterprises, but Charles described plans for “multiple data centers and flexible commercial spaces designed to support the growth of both local and tribal-owned businesses.” He also noted that the tribe had “secured the necessary land for the development of crypto mining facilities, and the required contracts are in place to ensure a reliable power supply for operations.” Notoriously energy-intensive, the mines built on tribal land may be exempt from environmental regulations enforced in other US locations.

Charles emphasized that the “protection of our tribal sovereignty remains our highest priority.” But CDEZ’S arrangement strikes John Quinterno as “a bit odd.” A consultant with South by North Strategies, a North Carolina research firm specializing in public policy, Quinterno, who specializes in labor economics, says members of a “libertarian economic movement with these kinds of weird alternate assets—many of whom appear to have no ties to North Carolina or the Catawba Nation—are suddenly popping up here.” So far, he hadn’t seen any tangible benefits for the Catawba. “If the tribe is going to let people come use its sovereign nationhood, where’s the return?”

The Catawba citizens I spoke with for this story haven’t seen any either. On a Wednesday morning in April, I drove to the reservation, passing through the sprawl from Charlotte as it gave way to rural farmland, fields edged by stands of bald cypress and river birch. Finally, I crossed the Catawba River, where the tribe’s artisans source the clay they’ve been using to make distinctive coil pots for thousands of years.

At the Catawba Senior Center, a new building with a handsome stone fireplace and floor-to-ceiling windows, I met Catawba elder Beckee Garris, a slight 78-year-old with long, wispy white hair and a purple T-shirt that bore the slogan “REMATRIATE.” She grew up on the reservation as one of nine siblings in the 1960s, when most Catawba didn’t have running water and were not allowed to use the bathrooms reserved for white people in nearby towns. Her great-grandfather was a part of the last generation fluent in the Catawba language; her memories of him speaking it helped prompt her to work on the first Catawba dictionary, published this year.

The Catawba’s history stands out even among other Native American tribes as particularly painful. Ravaged by smallpox and land disputes, the tribe dwindled in size. When the US government terminated federal recognition in 1959, its citizens lost all the benefits and protections afforded to Native Americans, limiting their ability to govern themselves. It took decades of organizing for them to win back any of those rights: In 1993, the tribe agreed to drop all claims on land that South Carolina took from them in exchange for federal recognition and $50 million to put toward land purchase, economic development, and other ventures.

“We should probably get Elon to help us build the infrastructure for some Indians.”

Even with those hard-won freedoms, the Catawba Nation has struggled. It had been embroiled in a bitter, yearslong dispute over its bid to build a casino about 45 minutes away from the reservation. In 2021, the tribe prevailed. When the casino is finished in a few years, it will be the largest on the East Coast. Even in its temporary quarters—a line of red trailers packed with poker tables and electronic slot machines—the casino is an economic powerhouse for the tribe. Each Catawba citizen receives biannual payments from the revenue. In December, Garris said, it was several thousand dollars—a boon when annual average income is $21,000, about half the national figure.

The casino, Garris said, was something everyone knew about and understood. You could get in your car and drive to where massive cranes ferried steel beams to the hulking structure taking shape, where the flashing and beeping game screens lined the trailers. CDEZ, on the other hand, was harder to wrap your mind around. There was no immediate tangible evidence of it, physical or monetary. Neither Garris nor the other handful of tribal elders I spoke with at the senior center had been told in advance about CDEZ, and they hadn’t heard about the legislature’s vote in 2022 to approve it. Garris learned about CDEZ only after it already existed. “My first gut reaction was that they’re using the tribe for their own benefits, since we have no knowledge of what it’s about,” she said. “It’s almost like ghost money that they tell you it’s there, but you don’t see it.”

About 370 miles northwest of the Catawba reservation, a very different spin on the network state is taking shape. I have written about the TheoBros, a group of mostly millennial and Gen Z ultraconservative men, many of whom proudly call themselves Christian nationalists. The TheoBros’ beliefs are extreme—most think that women shouldn’t be allowed to vote and that the Constitution has outlived its usefulness and we should instead be governed by the Ten Commandments.

Their highly networked movement communicates via podcasts and YouTube shows, on X, and at a seemingly never-ending series of conferences. Some are also in the process of acquiring physical space for their fellow believers. New Founding, an investment and real estate firm helmed by TheoBros Josh Abbotoy and Nate Fischer, says its goal is “to shape institutions with Christian norms and orient them toward a Christian vision of life, of society, and of the good.” Andreessen has invested in New Founding, and Fischer has invested in Pronomos Capital, Friedman’s startup societies venture firm.

New Founding is buying up land in rural Tennessee and Kentucky, where, according to its website, it aims to build conservative Christian neighborhoods “conducive to a natural, human and uniquely American way of life.” The communities will be designed around cryptocurrency and “digital self-governance,” all to promote a culture “in which our patrimonial civic rights, chiefly those of property, free political speech and civilian armament, can be maintained and perpetuated,” the project website says. The ultimate goal? “To be connected to broader economic vitality, and to project cultural and political power.”

When I emailed with Abbotoy, he didn’t provide details on plans to incorporate cryptocurrency into the communities but wrote that the people who have bought property so far “prioritize sovereignty in their personal lives, including digital and financial sovereignty. So naturally many of them love crypto.” He said about 60 households “have bought or moved to our target regions as a result of our efforts.” The website assures interested parties, “We see rising demand and capacity for new types of communities built around a shared vision for local life in America.”

But whose shared vision? The people who already live in the communities that New Founding is targeting have their own existing vision of local life, and many are not thrilled about the idea of wealthy Christian nationalists moving in and taking over. Last year, after Phil Williams of Nashville’s NewsChannel 5 aired an investigation about the movement, he followed up by speaking to locals. “Mainly, people are scared,” said a Republican county party official. “It scares me that they are very clear about taking over.” A local restaurant owner added, “I don’t want to lose what we already have.” In response to Williams’ reporting, C.Jay Engel, a TheoBro who moved to the area to help launch a New Founding community, posted on X: “Phil and the entire journalist class at large are terrified that conservative Christians are asserting themselves in the face of dwindling media power. This is why they double down on their strategies of provoking fear through distortion.”

Abbotoy says the network state concept doesn’t fully capture New Founding’s vision. He prefers the term “charter communities,” which he describes as places “chartered around particularized lifestyles or affinities…we emphasize traditional American values like faith, family, and freedom.” New Founding, he says, offers “a platform on which many localists can build their more particularized projects.”

Nevertheless, he says, Balaji Srinivasan is an influence. “I have definitely learned from his theories,” Abbotoy said. “Whether one is excited or horrified by Balaji’s predictions of the future, dismissing them out of hand isn’t good business.”

While Abbotoy says only about 40 parcels of land have been sold so far as part of New Founding’s project, he and other network state supporters are already trying to convince the Trump administration to scale up their vision—and there are signs the president is listening. On the campaign trail, Donald Trump proposed building “freedom cities” on federal land in rural areas. An organization called the Frontier Foundation drafted an open letter in February pushing Trump to act on that idea. Abbotoy helped launch the group, along with Tom W. Bell, the law professor who initially connected McKinney with the Catawba Nation.

The Frontier Foundation’s vision of freedom cities seems in line with the Trump administration’s move-fast-and-break-things efforts. The group’s policy memo explains that the new cities “should be exempt from certain federal regulation under special oversight by the executive branch.” When I asked whether New Founding had plans to lease any of its land back to the US government, Abbotoy answered, “This is unlikely at this stage, but I won’t rule it out entirely.”

In March, Friedman of Pronomos Capital told me that both the Frontier Foundation and a separate group called the Freedom Cities Coalition had met with the Trump administration, though he declined to provide any details. Earlier that month, Wired also reported that the Freedom Cities Coalition had engaged with the Trump administration. “The energy in DC is absolutely electric,” Trey Goff, chief of staff of Roatán’s semiautonomous zone Próspera, told Wired. “You can tell in meetings with the people involved that they have the mandate to do some of the more hyperbolic, verbose things Trump has mentioned.”

It’s soothing to believe that this whole movement might amount to nothing more than a few weird towns and rule-free data centers. But as the network state concept gains traction, Srinivasan has offered more unsettling details about the underlying ideology. In a rambling, four-hour appearance on the podcast Moment of Zen, Srinivasan describes his vision for a new San Francisco, one in which denizens would show their loyalty to tech companies by donning gray shirts.

The ultimate goal, after a kind of gang war for territory, would be for the “Grays” to drive out the “Blues,” Srinivasan’s word for progressives. The Grays, he says, will put up signs bearing tech company logos, only for “some crazy guy, addict” to “come and smash it” and replace it with Blue symbols, which he imagined as “syringes on the street, Greta Thunberg on the wall…It’s like a dog pissing and marking its territory. After you’ve got a building, you need to start figuring out how to control the streets.” Ultimately, the Grays would have access to exclusive zones of the city, enjoying added protection through a special arrangement with police, whom they would win over with lavish banquets.

If Srinivasan’s idea sounds like an especially heavy-handed piece of dystopian fiction, David Karpf, a George Washington University political scientist who is working on a history of techno-optimism, sees the network state as the latest in a long line of promised “futures that never arrive.” But in a way, the basic tenets of Srinivasan’s vision—the coercive alliance between government and power-hungry tech overlords, occupying zones with special privileges—seem consistent with the current political moment.

Srinivasan and his crew of technocratic thinkers are not fringe philosophers. They are among the intellectual stars of the MAGA movement. Efforts in line with the network state concept are happening at a local level—witness attempts by Y Combinator’s Garry Tan toward “reforming San Francisco and building the alternative tech political machine.” They’re also happening at the highest levels of government, as Musk uses the fig leaf of cost-cutting to hollow out the federal government, allegedly steal its data, and replace bureaucrats with AI.

For Friedman, the startup societies venture capitalist, that’s a thrilling development. “I’ve never been more excited,” he told me. “Massive deregulation, like more than Reagan, seems awesome.”

In March, Srinivasan made a suggestion to his 1.1 million X followers. “There’s a simple way to rebuild manufacturing in the US. Just give @elonmusk control of a huge swath of land surrounding Starbase, Texas, and allow him to set whatever regulations he wants.” As my colleague Abby Vesoulis reported last year, people who live in communities adjacent to SpaceX’s Starbase aren’t wild about the screaming rocket engines, debris, and wastewater Musk’s company generates. And in what Srinivasan dubbed a “Special Elon Zone,” there’s no real promise of jobs, because, he muses, the first things to build would be “mass-produced Tesla humanoids, which (if successful) could in turn build everything else.” (By 2030, Musk predicts annual production of 1 million such Optimus robots.)

In Próspera, where the Startup Societies Foundation conference was held, locals told the Guardian in 2022 that the deregulated island zone’s creators had originally pitched it as a “real estate and community development project.” Only later did they discover the plans to create a cryptocurrency-fueled autonomous city where landowners get more votes by acreage. After Honduran President Xiomara Castro made moves to end the project, its backers sued the country for $11 billion. “We don’t trust no one,” one Roatán resident told the Guardian.

Concluding his 2024 Brazilian podcast interview, McKinney urged listeners to think of incorporating a company in the Catawba’s zone as a form of retribution for a history of mistreatment. In the past, he says, Europeans would “subjugate what was seen as a less technologically advanced group, and because of that, tribes lost sovereignty.” But an aspiring entrepreneur could help exact justice for this disenfranchised people, and perhaps even enjoy a tidy profit. “By harnessing the power of markets and rule of law and technology and by being a part of that, you are leading towards that sort of historical justice,” he said, “as well as providing a space where you and your business can thrive.”

That’s certainly one way to think about it. Garris, the Catawba elder I met at the senior center, had a different take: “It’s like we’re grasping for straws, hoping that it’s going to bring something.” Her tribal government, she said, hasn’t always been transparent about its business dealings, leaving citizens to connect the dots on their own. Who’s to say the whole experiment won’t turn sour like Próspera?

That’s a question Americans should be asking more broadly, noted Karpf, who has called Srinivasan’s Network State “the worst book I’ve ever read” because of its utter sci-fi implausibility. While he’s less worried about the reality of a Special Elon Zone, Karpf is nevertheless concerned about Musk’s assault on the US government and the ways it seems to be pushing the same goals. “They are completely deconstructing the administrative state,” Karpf said, “implementing these ludicrous ideas with sort of a baseline of faith that surely, technological progress will just work out—and the lesson of history is, like, ‘No, it won’t.’”

This post has been syndicated from Mother Jones, where it was published under this address.