One evening in March 2017, Hoan Ton-That, an Australian coder building a powerful facial recognition system, emailed his American business partners with a plan to deploy their fledgling technology. “Border patrol pitch,” the subject line read. He hoped to persuade the federal government to integrate their product with border surveillance cameras so that their newly formed company, later named Clearview AI, could use “face detection” on immigrants entering the United States.

An immigrant to the United States himself, Ton-That grew up in Melbourne and Canberra and claimed to be descended from Vietnamese royalty. At 19, he dropped out of college and, in 2007, moved to San Francisco to pursue a tech career. He later fell in with Silicon Valley neoreactionaries who embraced a far-right, technocratic vision of society. Now Ton-That and his partners wanted to use facial recognition to keep people out of the country. Certain people. Their technology would put that ideology into action.

Clearview had compiled a massive biometric database that would eventually contain billions of images the company scraped off the internet and social media without the knowledge of the platforms or their users. Its AI analyzed these images, creating a “faceprint” for every individual. The company let users run a “probe photo” against its database, and if it generated a hit, it displayed the matching images and links to the websites where they originated. This made it easy for Clearview users to further profile their targets with other information found on those webpages: religious or political affiliation, family and friends, romantic partners, sexuality. All without a search warrant or probable cause.

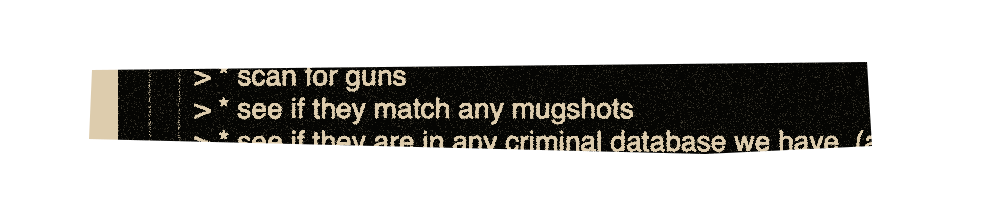

A diehard Donald Trump supporter, Ton-That envisioned using facial recognition to compare images of migrants crossing the border to mugshots to see if the arrivals had been previously arrested in the United States. His Border Patrol pitch also included a proposal to screen any arrival for “sentiment about the USA.” Here, Ton-That appeared to conflate support for the Republican leader with American identity, proposing to scan migrants’ social media for “posts saying ‘I hate Trump’ or ‘Trump is a puta’” and targeting anyone with an “affinity for far-left groups.” The lone example he offered was the National Council of La Raza, now called UnidosUS, one of the country’s largest Hispanic civil rights organizations.

By the end of Trump’s first presidential term, Clearview had secured funding from right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel, one of Elon Musk’s earliest business partners, and signed up hundreds of law enforcement clients around the country. The company doled out free trials to hook users, urging cops to “run wild” with searches. They did. Many departments then bought licenses to access Clearview’s faceprint database.

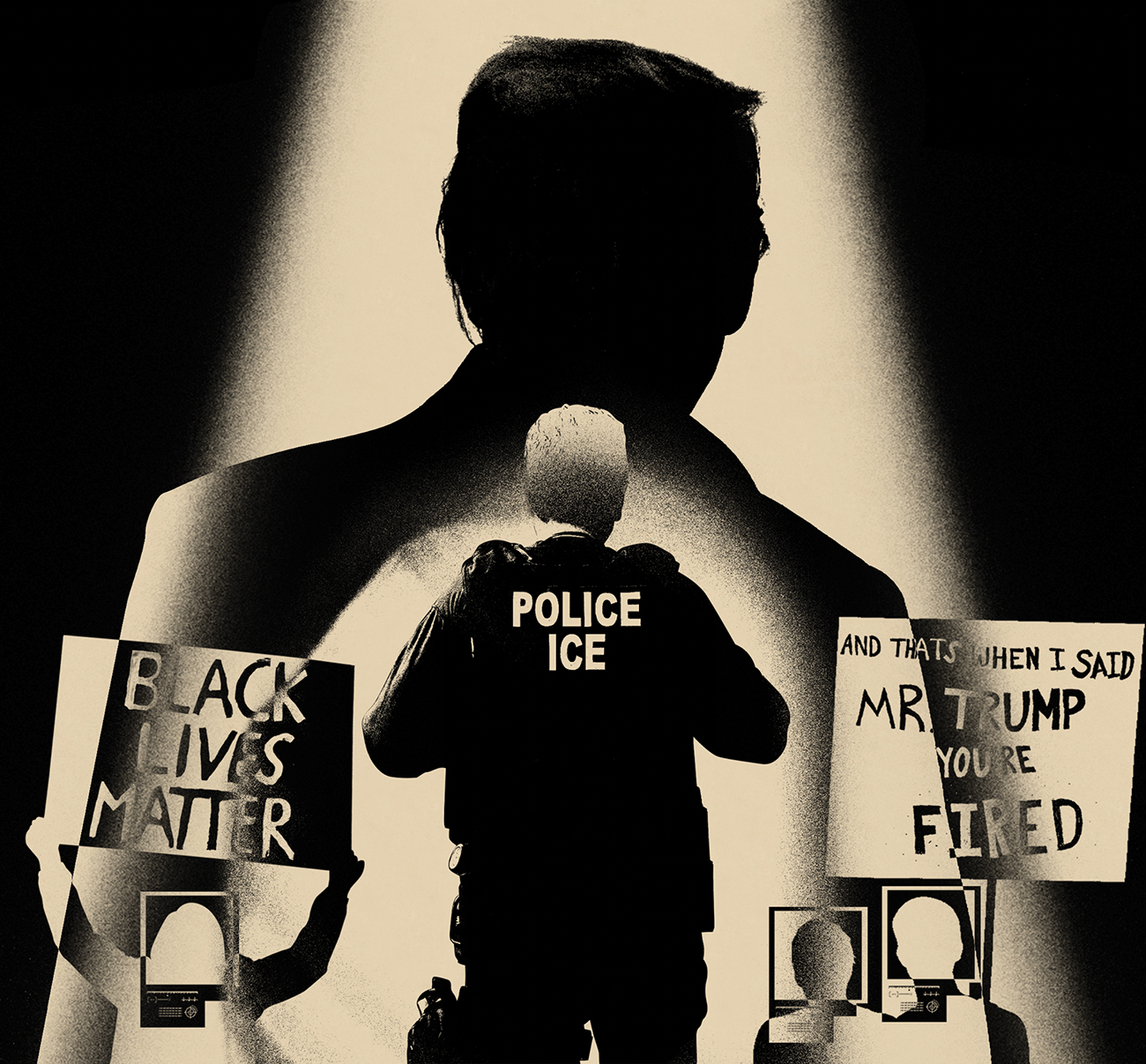

Since Clearview’s existence first came to light in 2020, the secretive company has attracted outsize controversy for its dystopian privacy implications. Corporations like Macy’s allegedly used Clearview on shoppers, according to legal records; law enforcement has deployed it against activists and protesters; and multiple government investigations have found federal agencies’ use of the product failed to comply with privacy requirements. Many local and state law enforcement agencies now rely on Clearview as a tool in everyday policing, with almost no transparency about how they use the tech. “What Clearview does is mass surveillance, and it is illegal,” the privacy commissioner of Canada said in 2021. In 2022, the ACLU settled a lawsuit with Clearview for allegedly violating an Illinois state law that prohibits unauthorized biometric harvesting. Data protection authorities in France, Greece, Italy, and the Netherlands have also ruled that the company’s data collection practices are illegal. To date, they have fined Clearview around $100 million.

Clearview’s business model is based on “weaponizing our own images against us without a license, without consent, without permission,” says Albert Fox Cahn, executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project.

In December, Ton-That, the face of Clearview since it was forced from the shadows, quietly stepped down as CEO and took on the role of president. In February, he abruptly resigned his new position, though he retains a board seat. When Mother Jones wrote Ton-That, who is now the chief technology officer at Architect Capital, a San Francisco-based investment firm, with questions for this story, he replied: “There are inaccuracies and errors contained in these assertions. They do not merif [sic] further response.” Ton-That refused to elaborate. Clearview declined to comment.

Replacing him as co-CEOs were Richard Schwartz, a co-founder of the company and a former top aide to Rudy Giuliani, and Hal Lambert, an early Clearview investor who runs a Texas financial firm known for its “MAGA ETF”—an exchange-traded fund that screens companies for their political contributions and buys into those that vigorously back Republicans. A top Trump fundraiser who served on the president’s 2016 inaugural committee, Lambert told Forbes in February that he planned to help the company pursue “opportunities” with the new administration, citing Trump’s mass-deportation agenda and anti-immigration policies.

Clearview is already well positioned to capitalize on Trump’s xenophobic plans. Today, one of the company’s top customers is US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a relationship cemented during Joe Biden’s presidency, as the agency inked bigger deals with the startup. Under the Biden administration, ICE records show, the agency deployed Clearview widely, even as officials there charged with monitoring the technology were in the dark about how it was being used and by whom. As the agency executes Trump’s emboldened mission—“Border Czar” Tom Homan has vowed to unleash “shock and awe” against undocumented immigrants—the dragnet surveillance outlined by Ton-That during the company’s earliest years may already be underway. (ICE did not respond to a request for comment.)

During Biden’s presidency, the trappings of oversight still existed. But Trump has fired many of the inspectors general who review the use of technology such as Clearview and guard against abuse. And Trump’s early actions have shown his administration has little regard for the legal, congressional, and constitutional guardrails that have constrained his predecessors.

Immigrants aren’t the only people at risk. With Trump pursuing “retribution” against his political enemies, Clearview offers a range of frightening applications. “It creates a really disturbingly powerful tool for police that can identify nearly every person at a protest or a reproductive health facility or a house of worship with just photos of those people’s faces,” says Cahn.

No federal laws regulate facial recognition, and many federal agencies have deployed Clearview for years with little accountability. Consider that the FBI—now run by Kash Patel, who has claimed FBI agents incited January 6, pledged to target journalists, and penned a book containing the names of officials he planned to settle scores with—is another major federal customer. Patel’s new deputy director, Dan Bongino, is a conspiratorial right-wing influencer who has used violent rhetoric about liberals and called for jailing Democrats. (The FBI declined to comment on its use of Clearview or on Bongino’s extremist views.)

I’ve reported on Clearview for years. This story, based on interviews with insiders and thousands of newly obtained emails, texts, and other records, including internal ICE communications, provides the fullest account to date of the extent of the company’s far-right origins and of the implementation of its facial recognition technology within the federal government’s immigration enforcement apparatus. It reveals how Ton-That, who obsessed over race, IQ, and hierarchy, solicited input from eugenicists and right-wing extremists while building Clearview, and how, from the outset, he and his associates discussed deploying the tech against immigrants, people of color, and the political left. All told, this new reporting paints a chilling portrait of an ideologically driven company whose powerful surveillance technology is now in the hands of the Trump administration, as it bulldozes democratic institutions and executes an authoritarian takeover.

Ton-That knows better than most how a picture posted online can come back to haunt you. As Clearview took off, he was confronted with a snapshot from his past that clashed with his effort to present himself and his company as apolitical. It showed him partying on election night in 2016 with far-right activists in MAGA hats. One fellow reveler, Charles “Chuck” Johnson, a political agitator with wide-ranging connections to Republican politicians and right-wing billionaires, was also Ton-That’s business partner. Smartcheckr, the company they founded with Schwartz, would later relaunch as Clearview.

In early 2021, Ton-That told the New York Times’ Kashmir Hill that his extreme views and associations were confined to a brief period in his life when he was “confused.” He offered a similar explanation a few months later when a documentary crew from France 24 asked him about his far-right ties. “I’m not a political person,” he said. “It’s wrong to assume my political beliefs just from a photo…That was a different time in 2016, a long time ago.”

But Ton-That’s path to radicalization began earlier than he let on, and his extremism was no fleeting dalliance. By 2015, he was interacting online with alt-right activists, including Milo Yiannopoulos and Mike Cernovich. Deleted social media posts also show him chatting with extremists such as Andrew “weev” Auernheimer, the longtime webmaster of the Daily Stormer, a neo-Nazi website. (Auernheimer, who has a large swastika tattoo and has repeatedly called for a genocide of Jews, denied to Mother Jones that he holds neo-Nazi views and claimed he was no longer involved with the Daily Stormer. He also said he never interacted with Ton-That but declined to address evidence of their communications.)

Pitch decks the company sent to potential investors and customers touted Clearview’s ability to surveil protesters and target people involved in “radical political or religious activities.”

By early 2016, Ton-That described himself as a lifelong libertarian who’d shifted further right over time. Along the way, he discovered the “Dark Enlightenment” neoreactionary movement, a fascist outgrowth of Silicon Valley’s radical libertarianism. He read the work of Steve Sailer, a longtime contributor to white nationalist publications and a proponent of “human biodiversity,” a racist pseudoscience favored by neoreactionaries. Like white nationalists, neoreactionaries reject egalitarianism and view America as weakened by feminism and diversity initiatives. But they make room within their elitist hierarchy for Jewish, Asian, and gay men—demographics, conveniently, common in Silicon Valley’s leadership class. Neoreactionaries consider themselves a high-IQ natural aristocracy and long for a corporatist strongman—a CEO monarch—to usher in what Thiel calls a “futuristic” version of the past, one in which technocrats rule as an ennobled caste. They view technology as the engine to remake society on their terms, an ambition that Thiel has never disguised.

“We were going to use technology to change the whole world to overturn the monetary system,” Thiel said in 2010, explaining the impetus for PayPal, the e-payment company he co-founded with Musk. “The basic idea was that we could never win an election…because we were in such a small minority. But maybe you could actually unilaterally change the world—without having to constantly convince people and beg people and plead with people who were never going to agree with you—through a technological means.” (Thiel did not respond to questions.)

As Ton-That radicalized, he grew friendly with Curtis Yarvin, an intellectual muse to Thiel, Vice President JD Vance, and other prominent right-wingers. Ton-That thought Yarvin was “brilliant” and spoke often and admiringly of “Curtis,” one source told me. The godfather of neoreaction in America, Yarvin (who did not respond to questions) believes democracy is a “dangerous, malignant form of government” and has argued for a soft coup and a purge of civil servants in favor of political loyalists. This “butterfly revolution,” as Yarvin called it in 2022, looks eerily similar to Trump and Musk’s blitzkrieg against the federal bureaucracy.

Neoreaction also led Ton-That to Johnson, a Thiel confidant who ran a far-right site called GotNews that published dirt on Black victims of police violence and Black Lives Matter protesters. “Am a reader of yours, like your work,” Ton-That wrote Johnson in May 2016, asking to be added to a Slack group Johnson had set up around a different project he had launched, WeSearchr, a crowdfunding platform that raised money for neo-Nazis and far-right causes. The Slack group was an online watering hole for a likeminded crowd, according to Peter Duke, another business partner of Johnson’s at the time who participated in the chat and who described it to France 24 in unaired footage.

“When you get to a point where you understand that democracy is fake, then you have to think about different frameworks for the way that people are gonna be ruled,” he said. “What we all had in common when we met was that we thought that neoreactionaryism was an interesting idea…The United States of America was founded on the idea that all men are created equal. And Curtis simply asked a question, as I remember it: ‘What if they’re not? What do you do?…How do you govern that?’…That’s what we talked about all the time.” (Duke declined to answer questions.)

Ton-That and Johnson quickly bonded. They brainstormed “alt-tech” ideas and a few months later, in early 2017, launched Smartcheckr, Clearview’s predecessor. Ton-That also got to know Duke and other radicals associated with Johnson, including Marko Jukic, a self-described extremist Catholic traditionalist who once argued that diversity is “corrosive to civilization”; Tyler Bass, a white nationalist who, according to his former girlfriend, attended the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia; and far-right influencer Douglass Mackey, who used a pseudonymous social media persona to disseminate Nazi propaganda and advocate for “global white supremacy.” (Jukic told Mother Jones that he now considers himself a centrist and that his neoreactionary writings were “exercises in theatrical hyperbole and comedic satire.” Bass did not respond to a request for comment. Mackey said he identifies today as a “moderately conservative Republican” and previously promoted white supremacy “mostly for shock and trolling.”)

Jukic, Bass, and Mackey would all go on to work for the facial recognition startup in some capacity. Jukic pitched Clearview to potential law enforcement customers. Bass oversaw a project with a real estate firm whose CEO was considering investing and wanted to test the tech, which the team piloted using a surveillance camera in the lobby of an apartment building to secretly harvest images of tenants and visitors. Mackey, who was later convicted of federal election interference for trying to dupe women and people of color into voting by text, did contract work for Clearview’s predecessor firm and briefly handled outreach to political clients interested in using what company promotional material characterized as “unconventional databases” for “extreme opposition research.” In 2020, while reporting on Clearview for HuffPost, I contacted the company to ask about Jukic and Bass’ roles. Clearview parted ways with both soon after.

Ton-That sought to recruit other extremists, too. He wrote in a November 2016 email that he wanted to “totally hire” Emil Kirkegaard, a Danish eugenicist who had scraped OkCupid and published the data of nearly 70,000 users. Kirkegaard, who did not respond to questions, had infamously advocated to legalize child porn and lower the age of consent to 13 or the onset of puberty.

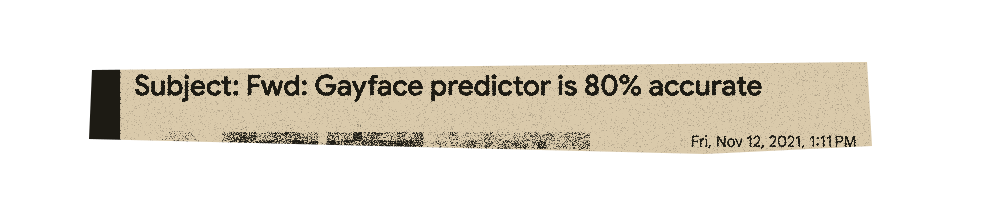

Ton-That called him a “total talent.” Emails show the CEO bounced facial recognition ideas off Kirkegaard, hoping to figure out how to identify gay people, or even predict criminality, from facial features.

Ton-That was fascinated by eugenics and admired the field’s founder, Francis Galton, who inspired Nazi “racial hygiene” programs. After digesting a letter by Galton that argued for Chinese immigrants to move to Africa and supplant the “inferior” Black race, Ton-That declared in an email that Galton was a “true prophet.” Among friends, he spoke often about IQ and race, wondering aloud about the intellectual superiority of half-Asian, half-white people like himself. He also consulted with Michigan State University physics professor Steve Hsu, a human biodiversity devotee who associates with Holocaust deniers and has spent years researching genetic differences among populations. In a 2017 email, Ton-That thanked Hsu (who did not respond to questions) for his work to “reverse dysgenic trends.”

Emails from the time show Ton-That reading and sharing articles from far-right publications such as Counter-Currents, VDARE, and Unz Review as he collaborated and socialized with a range of extremists and pro-Trump authoritarians. At an October 2016 event co-organized by future Stop the Steal leader Ali Alexander, Ton-That partied with Islamophobe Laura Loomer, right-wing sting artist James O’Keefe, and Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes, who initiated new members into his gang as Ton-That watched. Ton-That huddled at this event with Jeff Giesea, a Thiel lieutenant who helped the tech investor vet candidates for the first Trump administration. This was the far-right elite.

In a June 2017 email to Thiel seeking seed funding, Ton-That reported that he and his partners had landed their first facial recognition client: JPMorgan Chase. “We helped their security team vet each person attending their shareholders meeting to make sure there were no protestors,” Ton-That wrote. (JPMorgan denied using Smartcheckr.) But even as the company attempted to make inroads in the corporate world, its founders remained active in extremist circles. The same evening as the JPMorgan shareholders meeting, Johnson asked Ton-That to tackle another assignment. A technical error had fouled up a campaign on Johnson’s WeSearchr crowdfunding platform set up by the Daily Stormer’s Auernheimer to raise money for Andrew Anglin, the neo-Nazi site’s editor, who’d been sued for waging a harassment and intimidation campaign against a Jewish woman. Ton-That seemingly fixed the problem. Auernheimer and Anglin ultimately raised more than $150,000.

For at least the next year, Ton-That moonlighted as tech support for Johnson’s sites, sometimes helping extremists make and move money, usually cryptocurrency. When a co-founder of Johnson’s crowdfunding venture quit and left the team without a way to access the bitcoin they’d collected, Ton-That recovered the cryptocurrency, worth more than $150,000 at the time. Underscoring how vital Ton-That was to their operation, Duke wrote in a 2018 email, “Hoan is the only resource that has complete access and understanding of WeSearchr.”

As they grew their facial recognition company, Ton-That, Johnson, and Schwartz brought in investors such as Thiel and Naval Ravikant, an Indian-born technocrat who had encouraged Ton-That to move to the United States and became his first Silicon Valley mentor. Ravikant, who did not respond to questions, imagined a neofeudalist future of “small free cities with drone armies and skill-based immigration policies” and a “one bitcoin, one vote” system of government.

Another early backer was Hal Lambert, a former finance chair for the Texas GOP who runs Point Bridge Capital, the investment firm behind the MAGA ETF. Lambert, who served on Clearview’s board before becoming co-CEO with Schwartz, harbored his own fringe views. He claimed the George Floyd protests had turned into “George Soros funded riots” on social media and passed around a screed about how Floyd died from drug-induced “cardiopulmonary arrest,” rather than the knee of a cop on his neck. Like his business partners, Lambert wanted to deploy facial recognition to support a conservative agenda. In September 2017, after reading a Breitbart article that suggested out-of-state Democrats had flipped a close 2016 Senate race in New Hampshire, he emailed Johnson and Ton-That, urging them to use the tech to “identify exactly who the 5,000+ out of state fraud voters are.”

Conspiratorial ideas like these found traction within the company, where the founders exchanged emails indicating their belief that Democrats were cheating in other races around the country. They also appeared to buy into lies about antifascist activists spread by right-wing propagandists who conflate “antifa” with Black Lives Matter and other liberal protesters.

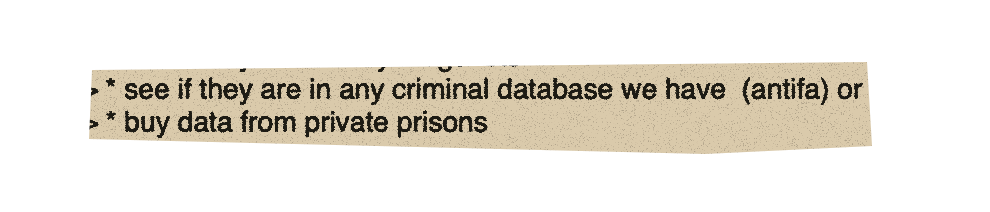

Paranoia about the “radical left” seemed to infuse their business decisions. As part of their plan to use facial recognition in apartment lobbies, they intended to scan the faces of tenants and compare them to mugshots. But Ton-That noted in an email that he also wanted to run them through “any criminal database we have (antifa)” or to see if they were “friends with criminals.” He assumed a link between leftist politics and criminality. “I think every real estate firm will sign up,” he told his co-founders. “Especially ones in diverse areas.” Schwartz, a 67-year-old New Yorker who ran Giuliani’s welfare reform program, which invasively profiled needy people and deprived them of assistance, loved the idea. “Quite Brilliant!” he replied. After Rudin Management, one of New York City’s largest real estate companies, signed on, the team reportedly collected about 70,000 videos from a lobby surveillance camera. “We beta tested their product for a brief period at one of our buildings nearly a decade ago,” a Rudin spokesperson said. “We chose not to deploy their software at the conclusion of that pilot.”

During Trump’s first term, Clearview made little distinction between bad actors and people exercising their First Amendment rights. Pitch decks the company sent to potential investors and customers, including scores of local law enforcement agencies, touted Clearview’s ability to surveil protesters and target people involved in “radical political or religious activities.” A pitch deck from April 2019 showed how Clearview grouped photos in its faceprint database, including a category it called “Protesters & Agitators.”

In July 2019, Johnson reached out to right-wing attorney Harmeet Dhillon, a Trump lawyer and Republican National Committee official. Dhillon was also representing Andy Ngo, a social media commentator who has made a career out of stoking fear about the “radical left” and who was preparing to sue several people who he alleged assaulted him at protests in Portland, Oregon. Ngo claimed they were antifascists. Dhillon, an election truther and anti-transgender activist whom Trump tapped to run the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, wanted to hunt them down. “Richard and Hoan can give you a copy of ClearView to help identify antifa,” Johnson told her.

“Thank you!” replied Dhillon, who said she would “send in a batch” of photos. (She did not respond to questions.)

Journalists were another target. In May 2017, Bass emailed Cassandra Fairbanks, a far-right activist whom the first Trump administration allowed into press briefings, to ask for the names and emails of reporters in the White House press pool. This would potentially enable Ton-That and his partners to surface social media accounts, pull photos, and, as Bass put it, investigate the “leanings” of the journalists. Fairbanks quickly sent the names and emails of eight reporters to Bass, who forwarded the details to Ton-That. “These shills are high-priority,” Bass wrote. “Dope this is going into smartcheckr,” Ton-That replied. The company later created a “Politicians – Academics – Journalists” category in its biometric database.

Smartcheckr and later Clearview shunned public attention. Clearview’s website was blank for a year. Eventually, it displayed a fake address and a cryptic tagline: “Artificial Intelligence for a better world.” Ton-That and Schwartz cautioned people using the tech to keep Clearview secret. They and Johnson preferred to hawk their product to their political network. They offered Clearview to anti-Muslim activist Robert Spencer and gave access to Sean Fieler, an anti-trans, right-wing Catholic hedge fund manager. They courted the family office of Shafik Gabr, a tycoon close to Egyptian dictator Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, and solicited venture capital in Beijing. They approached William Je, the financial adviser to Steve Bannon ally Guo Wengui, who was found guilty alongside Guo last year in a sprawling $1 billion fraud case.

While one former Clearview employee said the company tried to expand its potential customer base by courting “anyone they met,” including Democrats and progressives, the firm found few takers outside of the founders’ MAGA milieu. The Clearview team’s connections reached deep into Trump’s inner circle. They reportedly set up a free account for Rep. John Ratcliffe, now the CIA director. And Johnson met with Wilbur Ross, Trump’s first-term commerce secretary, and discussed facial recognition. The Clearview partners also pitched the Republican Attorneys General Association and the right-wing Club for Growth, offering its chairman what Ton-That described as “a motherlode of information that can help with oppo-research.”

During this stealth phase of its existence, Clearview’s most fruitful relationship was with the NYPD, thanks largely to Schwartz’s high-level connections, including to former NYPD Commissioner William Bratton, an instrumental figure in the post-9/11 expansion of police surveillance programs. Emails show that Ton-That planned a meeting with Bratton for August 2018. The NYPD began trialing Clearview shortly afterward. Although the department never signed a formal contract with Clearview, NYPD employees evangelized the tech throughout the law enforcement community.

“The company emphasizes the use within human trafficking and drug trafficking, but it’s highly unlikely that they would not be actively supporting deportation.”

Johnson, Ton-That, and Schwartz each owned a third of what was then still called Smartcheckr. But Johnson’s outré behavior—including publicly denying the Holocaust—had become a liability to his partners, who also contended that he wasn’t pulling his weight in their venture. In 2018, they formed a new company, Clearview, that initially excluded Johnson from ownership, according to court records. “I went from being a third owner of the company to being, like, written out of it entirely,” Johnson said in response to questions from Mother Jones. “And I said, ‘Well, I will just sue you guys.’” Eventually, Ton-That and Schwartz gave Johnson a 10 percent stake in the new company in exchange for his signing a November 2018 “wind-down and transfer agreement” that recognized his “good and valuable advisory services” but also required him to keep his mouth shut about his new ownership stake and prior work for the startup.

The narrative established by Clearview and most media coverage is that Ton-That and Schwartz excised Johnson from operations at this point. But Johnson continued to assist and advise his co-founders for nearly two more years, according to emails I obtained, connecting them with other potential investors and customers. When the Department of Defense scheduled a meeting in January 2020 for Clearview to pitch its services, the invite included Johnson. The following month, Ton-That sent his friend a proposal to compensate Johnson in Clearview stock for advisory services he provided to the company “with respect to developing, marketing and selling its technology.” In July 2020, Johnson helped Schwartz draft a letter for Rep. Matt Gaetz—a personal friend of Johnson’s—to send to top officials at the Department of Homeland Security, lobbying them to use Clearview to smoke out spies among the “400,000 Chinese nationals who enter the U.S. every year as foreign students.”

A February 2020 dinner in Los Angeles highlighted the company’s significance within the far-right movement. The dinner was one in a series of neoreactionary salons Johnson arranged for “young men of ability and distinction to talk about controversial or provocative topics openly, without fear of reprisal,” according to an invite he sent. Phones were to be checked at the door, unmarried women forbidden. When reached for comment, Johnson said Ton-That had attended a few of these events, including one where he met Steve Sailer, the human biodiversity writer whose articles about race and IQ Ton-That had read for years. Johnson could not remember if Ton-That had attended the Los Angeles dinner. But Sailer was the guest of honor. The next day, Sailer emailed Johnson some advice about Clearview. “One thing to look out for is cops abusing your system,” he warned, presciently. “Another thing: Hoan is a star, so the question is whether you want to ruin his cover and put him on TV.” (Italic Sailer’s. Reached by phone, he acknowledged knowing Clearview’s founders and then hung up.)

Ton-That was a star, at least among the far right. And he would soon be all over TV anyway, the result of a blockbuster January 2020 Times story that revealed Clearview’s existence and explored the privacy-shattering implications of the technology but did not examine its founders’ politics. While follow-up reporting, including the article I wrote for HuffPost, excavated Ton-That’s links to Johnson and other far-right figures, these associations didn’t stand in the way of Clearview landing its first big federal contract, in August 2020, with ICE.

But Johnson and Ton-That’s relationship finally unraveled. In October 2020, enraged by Ton-That’s comments to the media about his involvement with the company, Johnson erupted. “Effective immediately I no longer support the direction of the company nor its leadership,” he emailed Ton-That, Schwartz, and Lambert. It was a bitter parting. Johnson later sued Clearview and his former partners, who filed a still-pending counterclaim. (Lambert’s financial firm has also sued Johnson.)

When an irate Johnson spoke to the Times for a 2021 story, Ton-That and Schwartz asserted that he’d violated the secrecy clause in the “wind-down” agreement, which allowed them to buy him out of the company. They paid him $286,579.69.

Clearview kept rolling without Johnson. The breakthrough at ICE gave the company a foothold in the federal government. It also brought Johnson and Ton-That’s original vision closer to fruition. As Johnson bombastically described their early mission on Facebook, they were “building algorithms to ID all the illegal immigrants for the deportation squads.” Now, the company had found a willing partner in ICE, which has a history of racial and religious profiling, violating constitutional rights, and invasive data gathering and surveillance.

Since 2016, the agency’s employees and contractors have faced hundreds of internal investigations for misusing various databases of personal information. Department watchdogs investigated ICE employees and contractors for allegedly looking up each other and former lovers, giving information to friends and neighbors, and accessing databases in order to threaten and harass people or sell information to criminals, according to a 2023 Wired report.

Experts believe Clearview is likely already involved in deportation. “If Clearview AI tries to scrape all social media from all around the world, and there is a picture of an immigrant to the United States, then ICE could try to find out who that person is,” says Jack Poulson of Tech Inquiry, a watchdog group. “The company emphasizes the use within human trafficking and drug trafficking, but it’s highly unlikely that they would not be actively supporting deportation.”

Indeed, starting in mid-2019, ICE clandestinely piloted the tech through, among other units, its Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) division, which arrests and deports undocumented immigrants. A BuzzFeed News investigation found that ICE agents ran more than 8,000 searches during this period.

Records obtained by the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) and shared with Mother Jones indicate that ICE has mainly used Clearview in its Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) division, which traditionally conducts criminal probes into human trafficking and drug smuggling. But during Trump’s first term, HSI agents were deeply involved in deportation actions alongside ERO teams, participating in aggressive raids in sanctuary cities and sometimes arresting hundreds of undocumented workers in a day. Now, the units are teaming up again to round up immigrants.

In Trump’s first term, ICE also dispatched HSI agents to racial justice protests that erupted around the country after the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. HSI monitored other liberal or left-leaning events, labeling them in an internal document published by the Nation as “anti-Trump” protests, including a peaceful 2018 rally in Manhattan organized by a Democratic congressman to protest a white nationalist hate group.

The EPIC records reveal a culture of indifference at ICE about Clearview’s privacy and civil rights implications. It was a fancy toy that promised a low-cost investigative shortcut. “This can find faces in a crowd and/or it can show a photo in a crowd if you want to ID people he/she may associate with. It was amazing!” one ICE employee marveled. But Clearview spooked some people, including a Customs and Border Protection employee who emailed a colleague at ICE after learning the agency had the tool. “You guys use this?” the CBP staffer wrote. “Looks creepy as hell.” It was. An email from an ICE privacy officer noted that the agency “wants to use facial recognition to track people threatening its agents online.” Only after the Times broke news of Clearview’s existence, according to the records, did ICE conduct a privacy assessment that should have taken place before the agency deployed the tech.

The EPIC files also show that ICE supervisors had little idea how Clearview was being used and struggled to determine which units and agents had access. ERO and HSI had Clearview. But so did task force officers outside of ICE who work with federal law enforcement. More than 100 people connected to the agency were using Clearview around the world in places like Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; Rome; Manila, Philippines; and Ton-That’s hometown of Canberra.

During the Biden administration, demand for Clearview surged within ICE. On March 25, 2022, the agency held a “Clearview expansion meeting.” Lambert has said the bulk of the company’s $16 million in annual recurring revenue still comes from local law enforcement, but ICE has been Clearview’s steadiest customer, paying the facial recognition firm nearly $4 million.

In general, the federal government is hungry for facial recognition. The Department of Homeland Security is experimenting with using facial biometrics to monitor migrant children “down to the infant” and algorithmically predict how they will age so they can be identified if they cross the border years later. Under the Biden administration, CBP already used an app with facial recognition to screen asylum seekers trying to enter the country; like most similar technology, the app has shown a bias against darker-skinned people, blocking Black applicants from filing claims.

Between April 2018 and March 2022, Clearview was used by more federal law enforcement agencies than any other privately owned facial recognition system, according to US Government Accountability Office reports and public reporting. It was deployed by agencies including CBP; the FBI; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; and the Drug Enforcement Administration. Even the US Postal Inspection Service used Clearview, targeting Black Lives Matter protesters in 2020. Many of the agencies failed to comply with privacy requirements. Some told the GAO they didn’t use Clearview, only to be caught later by BuzzFeed News, which cross-referenced the report with a leaked list of federal agencies whose employees had run searches.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of local law enforcement departments have also embraced Clearview with even looser oversight. Clearview’s user code of conduct states that its search results are “not intended nor permitted to be used as admissible evidence in a court of law or any court filing.” But cops have used the search results, and nothing else, to secure warrants, rather than as leads to support further investigation. This practice has led to wrongful arrests and risks putting every American, not just every immigrant, in a permanent police lineup.

With Congress failing to act on facial recognition, a handful of state laws that protect residents’ biometric information have been the only tool to hold Clearview accountable. Notably, in 2020, the ACLU sued Clearview in Illinois, which led to a 2022 settlement banning the company from making its faceprint database available to most businesses and other private entities nationwide. Another lawsuit, now in California’s courts, was brought by immigrants and racial justice activists who accuse the company of “illegally acquiring, storing, and selling their likenesses, and the likenesses of millions of Californians, in its quest to create a cyber surveillance state.”

“They are making money off our privacy, our own spaces, our biometrics,” says Reyna Maldonado, a DACA recipient who owns a Mexican restaurant in Oakland and is a plaintiff in the suit.

An immigrant rights activist since her teens, Maldonado has publicly protested ICE. But she and the other plaintiffs allege in their suit that Clearview’s chilling effect has already undermined their free speech. “I’m a lot more careful about what I share. I feel like I can’t be fully open about my community organizing work,” Maldonado says. “People think this is only an immigrant struggle and it’s only going to affect those who are undocumented. The reality is they have even more information on people who are citizens.”

Sejal Zota, co-founder and legal director of Just Futures Law, a civil rights group that helped bring the suit, predicts facial recognition will be used even more widely during Trump’s second term. “We expect to see [it] extend from Trump’s alleged targets—immigrants—to the general public.”

In March 2024, the US Commission on Civil Rights convened experts at its headquarters near the White House to discuss the dangers of facial recognition. While immigrants were most at risk, privacy advocates told the commission, they were just the initial target. “[They] are canaries in the coal mines on civil liberties because they are positioned as test cases for policies that roll back all of our shared liberties,” explained Laura MacCleery, a senior policy director at UnidosUS, the same civil rights organization Ton-That mentioned in his 2017 Border Patrol pitch. Something had to be done, the privacy advocates agreed, before it was too late. But it was already awfully late. Facial recognition technology was thoroughly embedded in the nation’s surveillance infrastructure.

Sitting placidly at the panelists’ table, his long black hair spilling to the shoulders of his gray suit jacket, was one of the people most responsible for that outcome.

“As a person of mixed race,” Ton-That told the commission, “it is especially important to me that this technology is deployed in a way that protects and enhances civil rights.”

Information about Clearview’s ties to extremists was already public, but Ton-That faced not a single question about his background. Nor was he asked how, as a class-action lawsuit against the company alleged, violating Illinois law by collecting the “biometric identifiers and biometric information” of citizens without informing them was compatible with civil rights. In September, the commission issued a 194-page report that failed to mention Clearview’s radical associations.

The report did acknowledge, however, one of the achievements that Ton-That has trumpeted the most, including before the commission. Clearview, he said, had “played an essential role” in helping investigate the violent insurrectionists who stormed the US Capitol on January 6, an incident he described elsewhere as “tragic and appalling.” The attack had proved an enormous publicity boon for Clearview—and an opportunity to scrub the far-right taint from its image. In media interviews, Ton-That touted Clearview’s ability to track down MAGA criminals. The company published a case study on its website highlighting its role in the “arrest of hundreds of rioters in a short amount of time.”

The boasts struck a discordant note. The politics of Clearview’s founders aligned more closely with those of the rioters. Almost a year after the insurrection, Peter Duke, the founders’ neoreactionary ally, hosted Stop the Steal ringleader Ali Alexander on his podcast to push a conspiracy theory that the attack was a false flag operation by undercover FBI agents. Duke, who was in Washington on January 6, had photographed dozens of rioters at the Capitol who he suspected were federal provocateurs. “They’re not in the Clearview database,” he told Alexander. “I’ve checked.” Duke, who has said he once worked for Clearview as a consultant, took their absence as a sign of a coverup. He later repeated this claim on camera to France 24, explaining that he had friends at Clearview “run the faces.”

It was a startling admission. Clearview’s code of conduct prohibits use of the tech for “personal purposes.” But here was Duke talking about running off-the-books searches in an effort to whitewash an attack on American democracy.

“All of the evidence we have is that [Clearview] is a corporation that cares not at all about civil rights and that their founders have a potentially ideological agenda inconsistent with democracy,” says Emily Tucker, executive director of Georgetown Law’s Center on Privacy and Technology. “None of that has seemed to slow down their ability to get government contracts in the US or abroad.”

Nobody in a position to hold the company accountable seemed to care about its far-right DNA—and few wanted to consider that the threat to privacy and democracy might not be an unfortunate by-product of the tech, but rather a feature. Tucker said her organization discussed Clearview’s extremist ties with several Biden administration officials, as well as congressional staffers, and she was surprised and concerned by the lack of follow-up. Most media coverage of the company left the issue unmentioned or, worse, downplayed what was known—one interviewer for the financial magazine Inc. described the extremists at Clearview as “rogue employees” who had “infiltrated the company.”

In America, the debate about tech harms proceeds from the flawed assumption that tech is neutral. It’s the Silicon Valley version of “guns don’t kill people,” and it obscures the truth in a similar way. This smokescreen allows social media oligarchs to pose as impartial platform owners while their algorithms spread lies about Haitian immigrants, or an AI overlord to claim his tech is unbiased even as it amplifies election misinformation. Technology doesn’t exist in a political vacuum—indeed, it can be an ideological tool. A designer can imbue bias into their creation.

Today, there is no longer a need for Clearview to pretend to be apolitical. Lambert, the company’s new co-CEO, is already in business with both Elon Musk’s SpaceX and the Department of Defense through a separate satellite company, and he has made no secret of his desire to deploy Clearview as an instrument of MAGA rule. “Under the Trump administration, we would hope to grow more than we were able to under the Biden administration,” he told Forbes. “We’re talking to the [Pentagon], we’re talking to Homeland Security. There are a number of different agencies we’re in active dialogue with.”

In the emails I obtained, Lambert expressed a desire to “take down these lefties” and railed against the “communist academia left.” Unlike his predecessor, who at least paid lip service to the rule of law after January 6, Lambert helped to gin up unscientific and inaccurate analyses of voter data that Republicans used to back false claims of voter fraud after the 2020 election.

Even before the leadership shakeup became public, it was evident to the careful observer that changes were afoot at Clearview in anticipation of the new administration. Days before Trump was again sworn in as president, vowing to pardon the insurrectionists who attacked the Capitol in his name, the company updated its website. Deleted were any references to its role in identifying the far-right marauders who had laid siege to democracy.

Top image: Evan Vucci/AP; Getty (2)

Inside illustrations: Getty (3), Sean Zanni/Patrick McMullan/Getty, Stanton Sharpe/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty, Eva Marie Uzcategui/Getty, RIGHT: Getty (3), Roberto Schmidt/AFP/Getty, David Dee Delgado/Getty, Jim Young/AFP/Getty; Simone Fischer/Unsplash, Colin Lloyd/Unsplash

This post has been syndicated from Mother Jones, where it was published under this address.