Secret chemicals. A hush-hush atmosphere surrounding airborne pollution. Non-disclosure agreements preventing open discussion of industry impacts.

Some of the same transparency issues that reared their heads during the early days of fracking a decade ago are making a resurgence at the state and local level across the U.S., this time with new twists under the current federal government.

With the Trump administration slashing funding and staffing for programs that collect environmental data, and, in some cases, even forbidding the use of terms like “climate change,” the public’s access to this state and local information is more important than ever. The second Trump administration is silencing science even more aggressively than the first, “going after entire agencies and shuttering whole offices dedicated to addressing climate change, rather than individual people or policies,” Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law noted in April, calling that ultimately “more destructive.”

Take, for instance, Colorado. There, activists succeeded in convincing the state to require fracking chemical disclosures in 2022 – only to see those rules go unenforced today, with the state failing to collect an estimated $37 million in fines from violators, according to a recent report from the FracTracker Alliance, Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR), and Sierra Club Colorado.

In Virginia’s “data center alley,” researchers have uncovered broad non-disclosure agreements signed by public officials with big tech, keeping details about planned construction under wraps — and information about AI’s energy demand out of sight.

And in Louisiana, a new law is chilling community groups from sharing information about simple air pollution test results.

Despite the federal government’s efforts to conceal these serious environmental impacts, state and local community groups across the U.S. are fighting for the public’s right to see this important data.

“To anyone else who has thought about standing up to bad laws, do it,” said Caitlion Hunter, director of research and policy at RISE St. James Louisiana, one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit seeking to have Louisiana’s law tossed out as unconstitutional. “Your voice has incredible power.”

Colorado: The Galeton Geyser

Just before 6 p.m. on Sunday, April 6, the Galeton, Colorado, fire department got an alert from the oil and gas giant Chevron. A Chevron well had blown out, sending water likely laden with oil, gas, and chemicals rocketing into the air above the company’s Bishop well pad. Hundreds of responders raced to contain the blowout and begin clean-up efforts.

Less than a mile away from the site is Galeton Elementary. The eruption forced the school to close for two weeks, with students sent to attend classes at another nearby elementary school. One of those kids, fifth–grader Cole Ranalli, started calling the tower of oily wastewater the “Galeton geyser” in a student news broadcast about the incident — and the term stuck.

The well that blew out had been fracked earlier this year – meaning the water spraying from the well was likely laden with chemicals in addition to oil and gas. Chevron noted the blowout began after fracking had ended and pointed out that the company “discloses the chemicals we use on a third-party site called FracFocus.” And indeed, FracFocus reveals the company injected dozens of chemicals into the well.

But there’s a glaring gap on that list.

One entry simply reads “Organic surfactants: Trade Secret.”

The mysteries of “trade secrets” surrounding chemicals used during drilling and fracking have a long history of stirring up an enormous amount of public concern. In 2019, then-CEO of Colorado-based fracking company Liberty Energy, Chris Wright, now U.S. secretary of energy, drank a “frac fluid” — a four-ingredient blend mixed up on camera for the stunt — to highlight how some of the chemicals used in fracking can be non-toxic.

Of course, that’s hardly the full picture. Hundreds of scientific studies have shown wastewater from real-world fracked wells can be dangerous and often carries toxic and cancer-causing substances.

And indeed, Wright’s stunt seems to have failed to quench concerns in Colorado, where community organizers successfully pushed for a state law requiring mandatory disclosures.

Since 2022, a new law requires companies to disclose all of the chemicals used in oil and gas wells in Colorado — trade secrets notwithstanding. Companies don’t have to make their exact formulas public, but they need to reveal the ingredients used. That’s in part so that first responders, like the over 340 emergency workers who fought the Galeton geyser, can know what exactly to expect if people are exposed to oil and gas waste.

But Colorado’s reporting law is routinely broken, according to the May report “Oil & Gas Chemicals Still Secret in Colorado,” written by three environmental groups.

Across Colorado, over 30 million pounds of secret chemicals were injected underground at oil and gas sites since the 2022 law went into effect, the report found. That includes over 1,300 pounds of trade secret chemicals at the Galeton well, a FracTracker map accompanying the report shows.

“We don’t know what the local people, including schoolchildren at the nearby school, were exposed to,” said Ramesh Bhatt, chair of the Colorado Sierra Club Conservation Committee. “Unfortunately, this seems to be a pattern in this state.”

State-wide, chemical disclosures were available for just 439 of the 1,114 wells covered by the 2022 law — a compliance rate of just 39 percent, the report found.

Violations of Colorado’s 2022 “Oversight Of Chemicals Used In Oil & Gas”

law are so widespread that companies should now owe a stunning total

of $37 million in back fines. But the state hasn’t collected.– “Oil & Gas Chemicals Still Secret in Colorado,” 2025

Chevron, which became by far Colorado’s biggest oil and gas producer after its Noble Energy and PDC Energy acquisitions in 2020 and 2023, respectively, operated more than half of the wells that lacked chemical disclosures, the report noted. This includes the well where the Galeton geyser erupted, which is operated by Chevron’s Noble Energy.

The oil giant pointed to chemical suppliers and manufacturers, which it said are “ultimately responsible” for making chemical disclosures under the state law, in response to questions from The Guardian.

Companies that violate Colorado’s law could face fines of at least $200 per day.

“As you can imagine, it was not an easy bill to pass,” Bhatt said. “The law was hailed as the first of its kind in the nation. However, implementation of the bill has been far from satisfactory.”

Violations are so widespread that companies should now owe a stunning total of $37 million in back fines, the report estimates. But the state hasn’t collected.

Colorado’s Energy and Carbon Management Commission (ECMC) is charged with enforcing the law and overseeing the state’s more than 10,000 oil and gas sites.

“ECMC is communicating with regulated entities that are out of compliance with the reporting standards required by HB22-1348 [the 2022 law] and working to ensure widespread compliance,” spokesperson Kristin Kemp told DeSmog, adding that the commission was “evaluating next steps to obtain compliance, including potential enforcement action.”

Kemp declined to comment specifically on the report’s findings, saying that the agency’s experts had not yet reviewed the document. At a public meeting shortly after “Oil & Gas Chemicals Still Secret in Colorado” was released, ECMC Commissioner Mike Cross “committed to reviewing the PSR report and reporting back to the Commission about the claims made in the report,” Kemp added.

Cross has worked as an oil and gas industry attorney and brings “substantial oil and gas experience” to the commission, according to his ECMC bio.

Louisiana: Red Flags Under Wraps

In southwest Louisiana, near Cancer Alley, a community group called Micah 6:8 Mission sprang up in the aftermath of major Gulf Coast hurricanes and the COVID crisis, distributing food, cleaning supplies and other resources to those in need. In 2022, the group got a federal grant to purchase two air-quality monitors that could test for a handful of common air pollutants, and agreed to share their results with the Environmental Protection Agency.

On days with poor air quality, Executive Director Cynthia Robertson also posts an alert on Facebook and hoists a red flag outside her office so her neighbors know when it might be better to stay indoors – or at least she did, until very recently.

Under Louisiana’s 2024 CAMRA law, community groups now fear

they could face fines of up to $32,500 per day – or even

$1 million for ‘intentional’ violations – for talking publicly about evidence of airborne pollution, except under a narrow set of circumstances.

Under the Louisiana Community Air Monitoring Reliability Act (CAMRA) signed by Governor Jeff Landry last year, community groups like Micah 6:8 Mission now fear they could face fines of up to $32,500 per day – or even $1 million for “intentional” violations – for talking publicly about evidence of airborne pollution, except under a narrow set of circumstances.

“The LA statute mandates that you can’t talk about air quality unless you’re using the equipment that they want you to use,” said David Bookbinder, director of law and policy at the Environmental Integrity Project.

“Unfortunately, the equipment that they want you to use costs hundreds or even thousands of times more than perfectly good equipment that people can use to monitor the air in the communities,” he added. “We know that this equipment is satisfactory because in many instances, it was loaned by the EPA to these groups.”

Several other Louisiana groups have also stopped publishing air quality test results — although some continue to collect that data in the meantime.

But they’re not giving up: They’re also suing.

A lawsuit, filed in federal court in May by the Environmental Integrity Project and Public Citizen Litigation Group on behalf of Micah 6:8 Mission, RISE St. James, Claiborne Avenue Alliance Design Studio, The Concerned Citizens of St. John, The Descendants Project, and JOIN for Clean Air, alleges Louisiana’s CAMRA statute thwarts federal environmental laws and violates the U.S. Constitution’s protections for free speech and the right to petition the government for the redress of grievances.

“CAMRA was written and introduced by industry groups fearing what community air monitoring would reveal,” said RISE St. James’ Caitlion Hunter. “Because there is no state monitoring for many of the most dangerous chemicals released, industry’s numbers on emissions have been allowed to go on unchallenged.”

Bookbinder said that as far as he knows, no community groups have yet been fined for their air monitoring under CAMRA.

Nonetheless, the threat of steep fines has cast a pall over efforts to publicize air pollution test results from low-cost air monitors.

Johns Hopkins University Professor Peter DeCarlo, who joined the groups behind the lawsuit at a press conference announcement, said the problem is that there’s too little air testing — citing a lack of official data on ethylene oxide, a powerful carcinogen, as an example.

“Regulatory ethylene oxide measurements in Cancer Alley were not available when we performed spatial measurements of this chemical in February 2023,” DeCarlo said. “Our measurement data that we collected showed cancer risks that were ten times higher than the models from regulatory agencies — and this really demonstrates the need for these important measurements.”

Louisiana’s not alone in lacking federal air monitors. In fact, most counties across the U.S. are “air quality monitoring deserts, lacking even a single monitoring station,” a study published in April in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found — even as smoke from wildfires has increasingly undercut air pollution regulation. Almost half of all Americans now live in places that get failing air quality grades in the American Lung Association’s 2025 “State of the Air” report.

Immediately on taking office, Trump moved to cut federal air quality data collection further back, albeit in fits and starts. In March, the State Department killed off a global air-quality monitoring program that had tested air at U.S. embassies worldwide, taking down the AirNow program’s website. In May, the National Parks Service temporarily suspended air sampling at 63 national parks across the U.S.

But the worst hits to air monitoring could still be on the horizon. Trump’s proposed EPA budget for 2026 would slash categorical grants for state and local air quality management from $235 million this year to $0 in 2026.

“We believe in the power of neighbors helping neighbors,” Robertson said. “Because when government won’t protect us, we must protect each other.”

Virginia: Data Denied

If you’re looking for the heart of the artificial intelligence industry, you could arguably find it just outside Washington D.C., in a stretch of northern Virginia known as “data center alley.”

It’s believed to hold the biggest concentration of data centers in the U.S., drawn by the area’s internet infrastructure, which sees 70 percent of global internet IP traffic cross its fiber optic cable network, Virginia Beach’s “digital port” hub of international data cables, and the region’s relatively cheap electricity.

But if you’re looking for specifics, they’re hard to find.

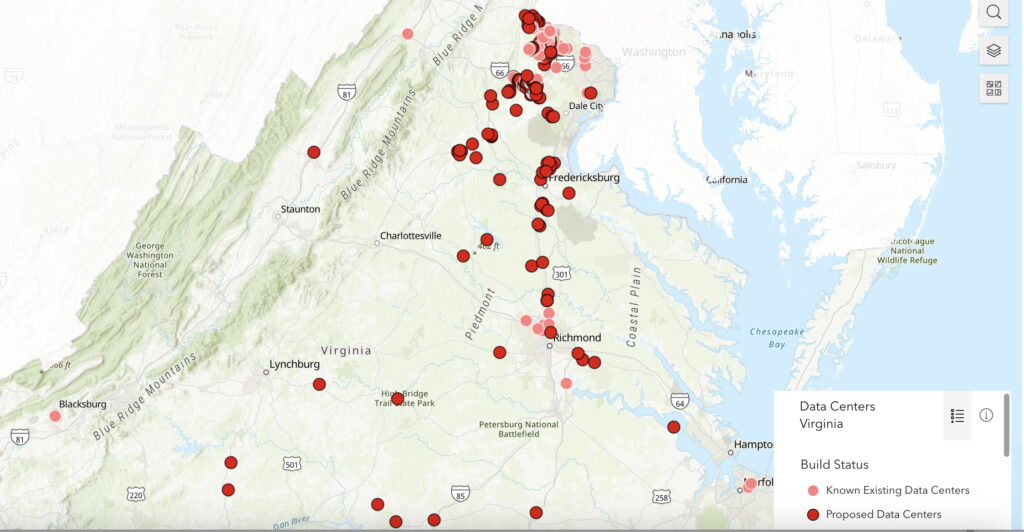

“How many data centers currently exist in Virginia? How many proposals are in the works? These are good questions,” the Piedmont Environmental Council, which attempts to track known data center projects in the state, says in its online mapping tool. “It’s also extremely difficult to provide an answer, given there is no publicly available dataset or state-level tracking of these facilities.”

One reason why data on data centers is so hard to pin down? Big tech companies, eager to keep their plans private, have struck non-disclosure agreements with public officials down to the local and county level, researchers from Virginia’s University of Mary Washington found.

“We thought it would be an interesting student project to just do an accounting, let’s learn about how much water is going to be used by these data centers, and how much electricity is going to be used, and how can we translate that in terms of carbon impacts,” sociology Professor Eric Bonds told DeSmog. “The students did fantastic work – but realized that this information is not available. So that shifted our research to think about, well, why isn’t this information available?”

So Bonds’ students filed public records requests for any non-disclosure agreements between local governments and tech companies or data center developers – uncovering dozens of such agreements.

The terms of many agreements caught Bonds by surprise, he wrote in a Virginia Mercury op-edin April, including language barring officials from discussing companies’ “business plans,” not just trade secrets.

“It’s very broad. It can cover a lot,” said Bonds. “And that can potentially prevent an interested public from knowing what is being proposed and developments that are in the works in their region.”

Those NDAs might be just the tip of the iceberg. Some experts advise data center developers to limit government officials to just seeing documents during video calls or visits, to reject requests for copies from public officials, or to preemptively redact information in communications that could become public. Some of the NDAs Bonds unearthed fit those patterns, including agreements with identifying information about the tech companies redacted and others forbidding public officials from acknowledging they had confidential information without the tech company’s sign-off.

Some big tech companies work behind shells to conceal their real backers – like one agreement between Prince William County, Virginia, and Sharpless Enterprises, which is reportedly a Google shell company.

“It would be nice to know what company intends to do business in the jurisdiction so members of the public can look into, what is the environmental track record of this company? Has this company made good on its pledges for tax revenue in the past? Or has it been a good neighbor in other locations?” said Bonds. “So that’s valuable information for the public to have.”

One of Trump’s first moves in office was to issue an executive order promoting a build-out of artificial intelligence infrastructure like data centers.

But it’s far from clear how many data centers will actually be built. Experts are warning electrical utility regulators about “phantom” data center demand, which can appear when one tech company explores building a project in several potential locations – and forecasters lack enough information to sift out the duplicates.

Individual data centers can demand as much electricity as a small city, amplifying the impacts from any confusion.

Electrical utilities nationwide are also legal monopolies – allowed to operate free of competitors but under the watch of utility regulators. That setup means that utilities have powerful incentives to build new power plants – and particularly big fossil fuel power plants.

The lack of public data also makes it harder to trace which big tech companies plan to rely on a fossil-fuel-powered electrical grid. Virginia’s Dominion Energy, for example, is drawing heat over plans to build a half-dozen new natural gas-fired power plants in the state, citing data center demand. But connecting new natural gas plants to a specific AI or other big tech project is made more difficult by the cloud of uncertainty surrounding data center development plans.

A coalition launched last year, the Virginia Data Center Reform Coalition, says it’s working to change that. They’ve backed Virginia bills aimed at giving the public more access to information about data centers’ water and energy demand. Those bills failed to make it to the floor this year, the Piedmont Environmental Council noted in April – but they’ve continued the fight in Virginia regulatory hearings.

At least 42 activist groups in the state are working to “slow, stop, or further regulate” data center development, the boutique research firm Data Center Watch found in a report this year. At least two major data center projects with a combined $900 million price tag were withdrawn in Virginia following local opposition, the report found, and seven other projects, with a combined value of over $45 billion, were delayed over the past two years.

“Data center challenges arise primarily at the local level, as most permitting decisions are made by local authorities,” the report says. “Consequently, even a supportive White House has limited control over delays arising at the local level.”

The post As Trump Unwinds Federal Oversight, States Become Battlegrounds for Environmental Data appeared first on DeSmog.

This post has been syndicated from DeSmog, where it was published under this address.